1.1 The Origin of the Universe

Abstract

The traditional understanding of Genesis 1:1 is that it is referring to a flat Earth with its blue sky above it, as described by ancient Mesopotamian cosmologies (Kramer 1981 p. 76; Claeys 1987 p. 8). Yet, as known from modern astronomy, there are myriads of other planets in the universe that are much older than the Earth. The first stars formed shortly after the big bang about 14 billion years ago (Bond et al. 2013), while the Earth came into existence only about 4.5 billion years ago (Allègre 2001 p. 120). Thereby, “in the beginning” cannot refer to our planet but must be applied in the first place to the invisible world of the angels and then to our visible physical world in which we live, even if other objects – including our planet – are also referred to.

Contents

The Spiritual World | The Big Bang | Ex Nihilo| The Laws of Physics | The Age of the Universe | Rules | References

Site Navigation

1.1.1 The Spiritual World

In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth (Gen 1:1).

Humans are limited in space and time. Therefore, when they speak or write, the meaning of the words must be determined from a single context. As a result, only one out of several possible meanings is valid. By contrast, when the Omnipresent and Eternal speaks, his words reverberate through space and time, kind of reflecting from the walls of the different levels they are referring to. So several meanings are possible, all of which are valid because they are bound by analogy. In particular, assuming that the first chapters of Genesis are God’s words, heaven and earth refer to different analogous realities that are all equally important. Just picking out one meaning and supersede it above all others leads to a very distorted picture. As discussed in the introduction, we will therefore assume that all possible meanings are valid solutions of the same “equation”.

The Hebrew word shamayim (heavens) in Genesis 1:1 is indeed used many times in the Old Testament and has several meanings. In Deuteronomy 4:19 and 1 Kings 8:30, for instance, this word is used to design the invisible world inhabited by God but also to describe the place of the angels (Gen 21:17; 22:11, 15) as well as the host of the Sun, the Moon and the stars (Dt 4:10; Isa 3:10). It furthermore designs the place where the birds fly around, that is, the lower atmosphere (Gen 1:20, 26). The word erets (earth) must be understood correspondingly because it has several significations as well. It means the whole world (Psa 72:19) as a counterpart to heaven (Job 28:24; 37:3) or the place of all nations (Isa 14:26) as well as a limited region, for instance, the land of Canaan (Gen 11:31; 12:5). So shamayim and erets are placeholders for different heavens and earths.

This can also be asserted because these terms are repeated several times in the account, which points to the creation of new heavens and earths. Genesis 1:6-8, for instance, mentions the creation of an expanse again called shamayim. Since Genesis 1:1 has already mentioned the creation of shamayim (in the plural), this must be considered a new heaven. Therefore, there must be several heavens, big and small ones with different properties. The same happens with erets (in the singular) in Genesis 1:9-10, where it is applied to the continent after Genesis 1:1 and 1:2 already used the same word to introduce different earths. Consequently, several earths must exist as well, big and small ones, which correspond to the big and small heavens to form together several heaven/earth dualities. This results in frame restrictions, pointing to the fact that big structures are often analogous to small structures.

Thereby, the invisible and visible world form together such a duality heaven/earth. Inside the visible world is found a smaller duality of this kind, that is, the space-time/matter duality because not only matter but also space-time is an entity that must have been created, as we are going to see. This gives us a rule for the further understanding of Genesis: like the different meanings of the words shamayim and erets, the duality heaven/earth of Genesis 1:1 is a structure that is referred to throughout the whole account. In turn, his duality successively refers to even more restricted universes that are embedded in the previous ones. The invisible and visible world is the first of this series of dualities followed by the restricted spaces of our physical universe, our galaxy, the Milky Way, our solar system and our planet. So Genesis 1:1 finally also refers to atmosphere/Earth and even ocean/continents, although other passages refer more explicitly to these dualities, as we shall see. These meanings have to be prioritized from outside to inside, which sets the angels above humans.

Angels are not cuddly cupids but fearsome and mighty creatures (Aquilina 2006 p. 7) that nothing can destroy whether in the invisible nor the visible world. Since they live outside our universe, they are not conditioned by physical laws whatsoever. This possibly means that they can travel faster than light such that they are able to get from one place to another in no time. There are myriads of them (Rev 5:11). If one of them got the permission to become visible to all humans and the mission to protect them, Superman would pale in comparison…

According to Colossians 1:16-17, the spiritual world of the angels did not exist from all eternity but has been created out of nothing:

For by Him all things were created, both in the heavens and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities – all things have been created by Him and for Him. And He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together.

This view has also been adopted by the Church on the Fourth Lateran Council in 1251 (Denzinger 1955 nos. 428, 1783). Furthermore, “the sons of God shouted for joy” when God “laid the foundations of the earth” (Job 38:4-7). The sons of God are angels (Job 1:6; 2:1). Therefore, they were present when God created the physical world. As a consequence, they have been created before it, although the Lateran Council uses the word simul with regard to the creation of the “angelic and mundane” worlds (Denzinger 428). However, this is not referring to time but to action in the sense that both worlds are created by God (Höfer & Rahner 1958 vol. 3 p. 870; Parente 1994 pp. 5-8).

This is supported by St. Augustine (the City of God Against the Pagans, book XI, ch. IX), according to whom shamayim primarily refers to the invisible world of the angels and erets to the totality of the visible terrestrial universe, and is also the point of view of other Church Fathers, even though St. Thomas and some modern theologians contest it (Parente 1994 p. 6; Aquilina 2006 p. 4). It is certainly no coincidence that shamayim is mentioned before erets. Therefore, assuming the completeness of the creation account, one can conclude that the angels were created “in the beginning” and the physical universe thereafter.

Like humanity, angels have a long history. Things happened that led to their fall. Satan is indeed a fallen angel created by God. But since all what God created is good, Satan was a good angel in the beginning. He became bad by his own fault and seduced others, the demons, to follow him. As a consequence, God created the physical world in order to prevail over Satan and salvage the whole creation. So without this fall, God would never have had the need to create us. This is a topic that will be discussed in more detail in chapter 2.2.

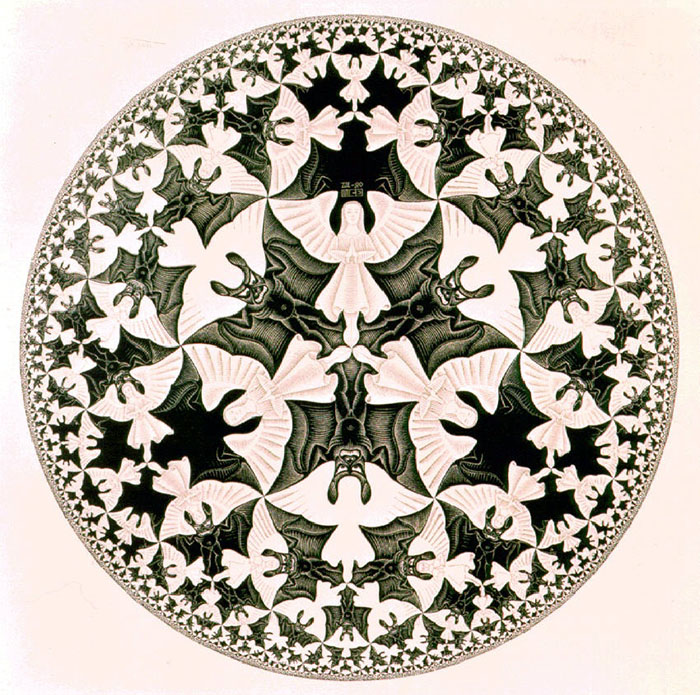

Figure 1: Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher imagined the angels as being part of a hyperbolically curved space.

Even though the Bible is full of mentions of angels, this, of course, does not prove their existence. While it is impossible to deliver a direct physical proof of the existence of a world that is supposed to be invisible and immaterial, this does not exclude at all that such a world exists. Since general relativity, predicting that matter warps space, it became indeed clear that there are more than the three spatial dimensions we are able to observe and measure. Therefore, it is possible that objects being part of an additional dimension may not be seen by people who can only perceive three dimensions. For instance, if the universe were a horizontal two-dimensional plane embedded in a three-dimensional space, any object floating above this plane would be invisible to people living exclusively in the plane and perceiving only two dimensions. Only when the object intersects the plane, it could be seen as a two-dimensional object. This fact can be extrapolated to more dimensions.

There are nevertheless indirect proofs from people who have encountered beings from the spiritual world. The most famous are probably Marian apparitions. While they are severely contested by atheists, non-Catholic Christians and often even by Catholics, there are scientific methods that show that the seers are indeed perceiving something that is normally hidden to human eyes. A series of such scientific surveys on the seers of Medjugorje has been conducted by a French medical team. For instance, they have examined the eyes of the seers during an apparition, showing that the menace and glare reflexes were absent during ecstasy, whereas it was present before and thereafter. Also, they did not react to a screen test, consisting of placing an opaque cardboard in front of their eyes during ecstasy. Furthermore, the eyeball movements studied on two seers showed that the movements stopped simultaneously at the beginning of the ecstasy and resumed at the end of it. And the seers’ gazes converged in the same direction, that is, towards Mary’s face (Joyeux & Laurentin 1985 pp. 86-88).

Marian apparitions have been around since the first centuries AD and seem to occur more and more frequently in modern times. The most famous shrines are in Guadalupe (Mexico), Fatima (Portugal) and Lourdes (France). Of course, there are also claims of Marian apparitions that are dubious and that the Church for this reason did not approve (Billet et al. 1973; Colin-Simard 1981). Other miracles undoubtedly exist too, but it would be out of the scope of this book to go into detail of such reports.

The spiritual world is not limited to angels because humans are invited to join heaven after their sojourn on earth. So they are also partly spiritual beings similar to angels, which is contested by materialists, who deny any spirituality. However, physicist Stephen M. Barr (2003 chs. 21-24) gives compelling reasons why humans have a soul, arguing that the human brain is not a computer but is endowed with feelings and consciousness, features that a computer will never have, also those based on artificial intelligence.

Now, I guess that only few people would deny that cats and dogs have feelings and consciousness. If true, the question arises whether there is any sharp frontier between animal species that have these features and others that don’t? In view of the smooth transition from lower to higher animals, it is impossible to clearly trace such a line. So the logical consequence of this is that every living being, including plants and microorganisms, have spirituality to some degree. Whether this can be called feelings and consciousness in the case of very primitive life is less important. What counts is that it must be some spirituality in whatever form. As a consequence, life cannot be reduced to death matter, not even a single bacterium. It must get its spirituality through the creation power of a spiritual being.

Even matter can be regarded as having spirit. Elementary particles like electrons have properties like charge and spin that cannot be explained in a materialistic sense, that is, as caused by still smaller materiel entities, otherwise they wouldn’t be elementary particles. Particles like protons and neutrons indeed consist of quarks that have properties similar to electrons. The string theory claims that the most elementary entities are strings that can vibrate in different manners. So they too make something and interact with their environment. How to explain these properties? It’s impossible, otherwise, here again, they wouldn’t be fundamental properties.

One may find ever more fundamental entities that get ever more simple, but their simplicity cannot go to zero because nothing can come out of zero. One could argue that when one reaches the point where no more fundamental materialistic explanation is possible, one reaches the spiritual world. Because spiritual is equivalent to immaterial, which is why materially inexplicable properties can equivalently be considered spiritual properties. And since they were not around since eternity, the most fundamental entities must have been programmed to behave in the way they behave. Instead of programmed, one could also say created.

1.1.2 The Big Bang

Before the big bang theory became established, it was thought that the universe is static and infinitely old, whereas time was considered to be absolute according to most philosophers of Antiquity, Newton’s contemporaries and nineteenth-century physicists. This would suggest that empty space is nothing and does not require to be created. So based on these assumptions, one may argue that there was no need for God to create space, that is, shamayim as supposed by Genesis 1:1. This first changed when Einstein theoretically discovered the expansion of the universe through his own equations in 1916. He was aware that this implied a beginning, as advocated by religious people, which he – a materialist, although he often spoke of God – was unwilling to accept. Subsequently, he altered his equations in order to obtain a static not expanding universe by introducing a cosmological constant (Ross 2001a p. 23; Barr 2003 pp. 37, 41-42, note 7 pp. 294-295; Jones & Lambourne 2004 pp. 228-229).

This did not prevent Alexander Friedmann in 1922 and Catholic priest Georges Lemaître in 1927 from proposing, on the basis of the same equations, that the universe was created in some kind of grand explosion. The first experimental confirmation of this purely theoretical hypothesis was announced by Edwin Hubble in 1929 with his observation that all galaxies drift apart from each other, which implies that in the distant past they must have been so close together as to form a single mass. However, this did not root out the mistrust towards a beginning of time because it had the smell of creation (Krauss 2012 pp. 4-6). In 1948, Hermann Bondi, Thomas Gold and Fred Hoyle proposed indeed the so-called Steady State theory in order to avoid a beginning. It was also Hoyle who coined the term big bang in an attempt to discredit Lemaître’s cosmology (Ross 2001a p. 28; Barr 2003 pp. 38-39, 42-44). Only when the cosmic microwave background (CMB) – an afterglow of the big bang – was discovered in 1965 the expansion of the universe hesitantly began to be accepted (Hawking 1998 pp. 49-50; Barr 2003 pp. 45-46; Whorton & Roberts 2008 pp. 299-300; Jones 2017 pp. 48-76).

The big bang implies that space and time as observed in our world had a beginning. Mathematically, space can be formulated in different manners. The oldest and simplest model is Euclidean space. In two dimensions, this is simply a flat and infinite surface, which can be extended to three or an arbitrary number of dimensions. More sophisticated concepts came up in the 19th century with Riemannian geometry, according to which shapes like a circle line or the surface of a sphere are closed and curved spaces. Also infinite open spaces are possible like hyperbolic surfaces, for example (Hartle 2003 pp. 386-387, Jones & Lambourne 2004 pp. 224-226).

Intuitively speaking, a curved Riemannian space is the locus of the shape alone, the place outside does not make part of it. Even though such spaces can be thought of being embedded in a space of higher dimensions, it could not be detected physically by intelligent beings living in these spaces because any physics are thought to take place exclusively inside them. As a result, their inhabitants could not go elsewhere and would perceive nothing from the outside. Worms on a circle line, for instance, could not cross each other because there is no escape from the line. This is why cosmologists usually do not ask questions about such hypothetical space outside of the universe. However, as noted in the previous section, the spiritual world could be located there. On the other hand, cosmologists have the ability to detect the curvature of space (Hartle 2003 pp. 13-18). Relying on these concepts, Albert Einstein developed his general theory of relativity in 1915, which is the basis for theories on the evolution and shape of the entire universe.

Cardinal Schönborn (2007 p. 40) asks: “Where is the universe expanding into? Is it expanding into space?“ He answers, in accordance with cosmologists, that there is no space outside the universe, so it cannot expand into preexisting space, which is debatable. But in any case, the scattering of all galaxies must be considered an intrinsic expansion of space. It is the room between the galaxies that increases, which is often compared to the expansion of the surface of a balloon being inflated: any given point on its surface gets further apart from each other. In a similar way, each galaxy is withdrawing from all others (Reeves 1988 pp. 48-49; Hawking 1998 p. 45; Davis 2002 p. 26; Barr 2003 pp. 40-41; Ross 2008 p. 98). However, it is not because physically it is not possible to detect space outside our universe that it does not exist. Even if the universe is three-dimensionally flat, it is mathematically no problem imagining it embedded in a higher-dimensional space, as a flat two-dimensional plane, for instance, can easily be thought of making part of three-dimensional space.

The expansion of the universe implies that the big bang was not an explosion in the ordinary sense of a deflagration from one point into preexisting space with locally different expansion rates. This would have led to a chaotic dispersal of matter in the universe (Ross 2001a pp. 27-28), while in reality it is very uniform in any direction when observed on large scales (Jones & Lambourne 2004 pp. 217-218; Hartle 2003 p. 363). So the expansion occurred everywhere at the same rate. Assuming that the universe is infinite, it was so at every moment of its evolution and therefore also at the beginning, as there can be no transition in time from finite to infinite (Barr 2003 p. 40). Therefore, the amount of matter in a uniform and infinite universe would be infinite as well, although in the observable universe it is finite. From a theological viewpoint, this is rather strange and unlikely because only God is eternal and infinite. All what he has created had a beginning and is finite.

The universe is filled with all kinds of energies. In the beginning, it was dominated by radiation, which was transformed into matter according to Einstein’s famous equation E=mc2, connecting the energy E with the product of mass m and the square of the speed of light c. There are also other forms of energy like kinetic energy due to the movement of the galaxies, gravitational potential energy and vacuum energy. The sum of all these energies per unit volume yields the energy density symbolized by the Greek letter W (Omega), which can be measured experimentally. W determines the shape of the universe. Three main models enter into question: if W is equal to one, the universe is open infinite and Euclidean flat; if less than one, it is also open infinite but hyperbolically curved; if greater than one, it is closed finite and spherically shaped (Hartle 2003 pp. 384-387; Jones & Lambourne 2004 pp. 246-251).

Let us return to our question if space may be considered a real entity on the same level as matter. This must clearly be answered affirmatively because space has properties like curvature and expansion. Naught cannot have any properties, it is just nothing. The vacuum energy density, also called cosmological constant or dark energy (Jones & Lambourne 2004 p. 248), is not very well understood at the time of writing. In any case, it contributes about 70% to the overall energy density, otherwise the universe would not behave as it behaves, that is, perform an accelerated expansion as observed in 1998 by Saul Perlmutter and colleagues, for which they won the Nobel Prize in physics in 2011 (Jones pp. 130-132, 433). Until then, it was thought that the expansion would slow down because of gravity and finally collapse.

By the way, dark energy must not be confused with dark matter, which is responsible for the constant speed of stars in spiral galaxies: taking into account only the visible matter, the rotation speed should decrease with increasing distance to the center, which is not observed. Vera Rubin, who discovered this phenomenon in the 1970s, concluded that invisible matter, or dark matter, must exist, causing the constant speed (Jones 2017 pp. 82-83).

As a result, even the vacuum, which for a long time has been associated with nothingness, has a vastly complex structure on a comparable level than matter. During so-called quantum fluctuations, particles and antiparticles can spontaneously emerge out of the vacuum within time intervals governed according to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. In other words, a certain amount of energy to produce particles can be borrowed from the vacuum within a limited time interval. The more energy is borrowed, the shorter the time interval, and vice versa. After that time, the particles must annihilate each other in order to respect energy conservation (Hawking 1998 pp. 109-110; Hartle 2003 p. 290; Jones & Lambourne 2004 pp. 352-355).

This has an important consequence: if we assume that God created all things, he also must have created space in a similar way than matter. Thereby, shamayim and erets (Gen 1:1) indeed refer to the whole physical world, of which the big bang marks its beginning (Ross 2001b p. 18). Space and matter as well as time are inseparable and not absolute and infinite like in Newtonian mechanics. They have a beginning, even though God previously created the spiritual world. In this world, the notions of space and time must have another meaning, though. So it is adequate to say that time as defined by physical processes, like for instance the rotation of the Earth around itself or the number of oscillations in a quartz clock, only began with the big bang.

As mentioned above, materialists don’t like such a beginning. This is why it comes as no surprise that a number of speculative alternatives to a beginning have been proposed. The most prominent scenario was an eternally bouncing universe: when the matter density in the universe is high enough, gravity would slow down the expansion until a maximum size is reached. After that point, the universe contracts and eventually ends in a big crunch. This is like stones that are thrown into the air and then fall back to the ground. Thereafter, a new big bang occurs and the same scenario repeats itself endlessly. This suggests that in the past there were already an infinite number of such cycles. So this model would not require a beginning.

But it faces several difficulties. In fact, it is not clear how it could bounce according to the known law of physics. Furthermore, the universe would be a kind of perpetual motion machine, which is an impossibility according to the second law of thermodynamics. Also, entropy would increase from one bounce to another according to the same law, which would be manifested in some form. Finally, what is observed is an acceleration rather than a deceleration of the expansion. This is why this model has been largely abandoned by the scientific community (Davis 2002 pp. 26-29 Barr 2003 pp. 47-61).

Another speculative model that seeks to circumvent a beginning is the Hawking-Hartle proposal, according to which space-time forms a finite surface with no boundary or edge. In other words, time is supposed to emerge gradually from space without having an origin nor a singularity at time zero, where the usual laws of physics break down. However, this attempt to unify general relativity and quantum mechanics is not without problems either (Hawking 1998 pp. 138-146; Davis 2002 pp. 32-34).

1.1.3 Ex Nihilo

Besides a beginning of time, the big bang also suggests that it popped out of nothing, which is something materialists don’t like either, insofar as they claim that matter is the only thing that exists. Therefore, the fact that it did not exist from eternity but suddenly came into existence from nothing would completely crumble their world view because its creation would necessitate a supernatural event. In fact, a beginning of time imperatively also implies an origin of space and matter. In other words, “before” the big bang there was nothing that could have been observed and measured physically.

The Christian tradition from the second century – so long before the advent of modern science – has indeed interpreted Genesis 1:1 as an ex nihilo (out of nothing) creation at the beginning of time. This understanding was continued by the Church and formally defined as a dogma of faith in 1215 by the Fourth Lateran Council and reaffirmed at the First Vatican Council in 1870 (Denzinger 1955 nos. 421, 1805). Among the ancient cosmologies of the world, Genesis is practically the only one to propose an ex nihilo creation in the beginning of time (Davis 2002 pp. 21-23, 26).

So what is left for the materialists to explain is how the universe came into being from nothing – not by a supernatural act – but by natural means. In 1973 Edward Tryon, a physicist at Hunter College in New York, argued in a seminal paper entitled Is the Universe a Vacuum Fluctuation? that the overall energy of a closed universe might be balanced by its net gravitational energy. In such a case, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle would no longer restrict the borrowing of energy to a very short time but allow it indefinitely since no energy at all is borrowed. From there, he evokes the possibility of a vacuum fluctuation being at the origin of the universe. This idea has been adopted by many cosmologists, including Stephen Hawking (1998 pp. 133-134). As the debate is still ongoing but no conclusive evidence has been found (Davis 2002 pp. 30-34), Tryon’s paper is reminiscent of a bone thrown into a pack of hungry hyenas, which gnaw on it to this day, even though there was never any meat but only its smell on it.

In fact, the zero energy of a closed universe is a myth, to which materialists clinch because it is a necessary condition for a universe out of nothing. In order to theoretically prove the zero total energy in such a universe, “pseudotensors” are often used. However, when changing from Cartesian to spherical coordinates one obtains another result (Berman 2009), which shows that the whole calculation is wrong because geometrical and physical quantities like lengths, angles, masses, energies, and the like must be invariant to any change of the coordinate system because under such a transformation an observer remains exactly at the same position in space and time. So this result is just as much pseudo as the tensors that are used to obtain it.

Lawrence M. Krauss, the counterpart of Richard Dawkins in the field of astrophysics, repeatedly claims in his bestselling book A Universe From Nothing (2012) that in a flat universe the average Newtonian gravitational energy is precisely zero, stressing each time that the observational data strongly suggest that it is flat (pp. 148, 149, 151, 152). But further on he correctly admits that this is not the whole story, that gravitational energy is not the total energy of any object in the cosmos and that there is also rest energy according to E=mc2. He could also have mentioned the kinetic energy of all the expanding galaxies (Hartle 2003 p. 377). He then appropriately continues to argue that in order to take into consideration the total energy of the universe one has to pass from Newtonian mechanics to general relativity, according to which it is not a flat but a closed universe that has zero energy (pp. 165-167). However, according to his previous repeated claims the universe is flat. So why should we now suddenly believe that it is closed without giving further arguments?

Fulvio Melia (2022), from the University of Tucson, reports that over the past half-century many such attempts have been made using a variety of approaches. But he questions whether all these treatments can be correct, given that the definition of what kind of energies contribute to the total energy is not consistently described. He also mentions that these calculations are suspicious because a zero-energy universe is a preferred answer as it is a necessary condition for a universe out of nothing. After pointing to some inconsistencies in Tryon’s paper, he states that the questions one may ask regarding these calculations – including pseudotensors and Krauss’s definition of nothing – seem to be endless, even beyond scientific exploration.

A zero-energy universe is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for its emerging out of nothing. In other words, even if the total energy of the universe were zero, this would not automatically cause it to come into existence out of nothing. As discussed in the previous section, a quantum fluctuation is a property of space, which is not nothing. So this would not answer the question of where space came from to allow a fluctuation since space wasn’t created until after the big bang. Here we are obviously caught in a circular reasoning: what came first, the big bang or space? This is similar to the old question: which came first, the egg or the chicken? Besides this, no answer is given to the question why spontaneous particle creation should also apply to the creation of an entire universe.

This discussion about the emergence of the universe from nothing reminds me of a very simple calculation: let’s equate nothing with the number zero. How can zero become another number when we have nothing more than zero at hand. Adding zero to another zero still yields zero, even if this is done infinitely. Also multiplying zero with zero yields zero, whereas dividing zero with zero is not allowed mathematically. Integrating zero would yield a constant or the cosine of zero would yield the number one. But we don’t have integration or other mathematical operations at our disposal because we are inside naught, where we are even not supposed to be, because we are something. In a strict mathematical sense, even zero is something. So this comparison is therefore a bit lame. But I am sure that an exceptionally convinced atheist has an answer for how to create a non-zero number with zero without using mathematics.

Lawrence Krauss is desperately doing this in his book. While I was reading it, he inevitably reminded me of a magician who tries to conjure a rabbit out of his hat, seemingly out of nowhere just by saying abracadabra. However, he doesn’t even come close to David Copperfield because one can see the rabbit crawling around in his sleeve before. The audience applauds anyway because they don’t really care whether the rabbit already existed before or not. The main thing is that the show entertains them and they can rely on a well-known guru who reinforces their atheistic world view, which in any case they already had before the show.

In the preface, Krauss first discusses how nothing must be defined. He agrees that empty space is not really nothing (p. xiv). Apparently, he debated a lot with theologians who opposed him when he claimed that space and time can appear out of nothing. They also contradict him when he speculates that the laws of physics might have arisen spontaneously out of nothing. Finally, he acknowledges their requirement that anything that has the potential to produce something is not in a state of true nothingness (p. xv). In the last three chapters, he nevertheless tries to show that something can come out of nothing as defined by those theologians. However, his wishful thinking is so obvious that he is unable to convince anyone else but himself and his audience that is just as much in desperate need to believe in his hocus-pocus. As Krauss postulates himself, a true scientist should always be open to every possibility, whether he/she likes it or not (pp. xii, 142). On the other hand, it is obvious that he does not like at all the evidence that nothing can come out of nothing and will never adhere to it. So he is in contradiction with his own rules.

One can easily stick a label on everything that exists. For obvious reasons, this is not as evident with naught, which is like a black hole that cannot be seen directly but only by the gravitational effects it exercises on the neighboring matter. So naught must be imagined by representations. Naught is indeed echoed in nature by numerous images the Creator has woven into his creation as messages to us humans. Darkness, as represented by night, for example, is such an image. The Jews start indeed a new day at sunset in order to respect the passage from nonbeing into being when the universe was created. As we are going to see (sec. 1.2.3), the early universe was plunged into total darkness until it was illuminated by the first stars, which took some time and further underlines the fact that it was born out of nothing. Physical death is also an image of naught, into which we return after having come out of it, just as spiritual death, as will be discussed in more detail in section 2.4.1.

In conclusion, the big bang has four main characteristics: 1) it had a beginning, 2) it was a supernatural event, 3) space and 4) matter were created out of nothing. These are perfectly encapsulated by the first verse of Genesis:

| In the beginning | God created | The heavens | and the earth. |

| beginning of time | supernatural event | creation of space | creation of matter |

Table 1: the big bang referred to by Genesis 1:1.

1.1.4 The Laws of Physics

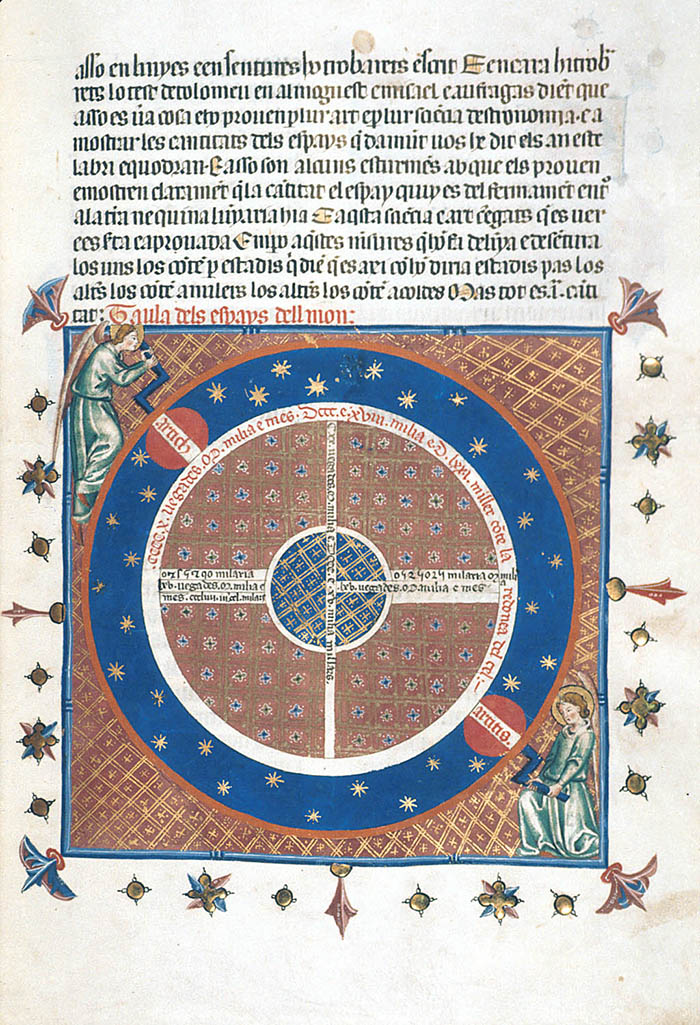

In the Middle Ages, it was thought that any moving bodies sooner or later come to a standstill, which was based on the experience of daily life. The concept of friction, which is responsible for the slowing down, was still unknown. Therefore, observing the apparently constant movement of the heavenly bodies, one assumed that they got some supernatural force to keep them going on, in other words, that they were driven by angels, as illustrated by figure 2. But then Galileo Galilei discovered that bodies fall equally fast in a frictionless vacuum, no matter whether it is a feather or a lead ball. When still later Isaac Newton formulated the law of inertia, it became clear that the celestial bodies did not have to be driven by angels because in the space where they move is no air slowing them down by friction.

Figure 2: The medieval view of celestial mechanics driven by angels.

Krauss (p. 145) concludes from this that angels and the supernatural do not exist… He also suggests that religion is hindering the development of science by claiming (p. 144) that theology has made no contribution to knowledge in the last five hundred years since the dawn of science, which he attributes to Galileo and Newton (p. 184). If one assumes that he restricts knowledge to the natural sciences, this should not surprise him because theology is not directly concerned with natural science. Therefore, theology has contributed no more to natural science than the invention of knitting contributed to the development of shoemaking.

However, when theology is extended to religion or religious people, then the picture changes radically. Between the 12th and 15th centuries, the Muslim world made major contributions to mathematics and medicine. Copernicus, the discoverer of the heliocentric system, was a Catholic canon. Galileo Galilei, a pious Catholic (Sharratt 1996 pp. 17, 213) who defended the Copernican view and was unfortunately sentenced by the Church for this, is often pulled out of context by atheists to denigrate religion and the Church. The matter of fact is that this exclusion was an anomaly on the part of the ecclesiastical authorities. The Church overwhelmingly supported the scientific inquiry of creation and many important scientific figures were deeply religious men, including Kepler, Newton, Ampère, Maxwell, Kelvin, and so on (Barr 2003 pp. 8-11).

Krauss (p. 160) also cites Einstein who asked himself “whether God had any choice in the creation of the universe”. Krauss indeed falls into the same trap by stating that “Newton’s laws severely constrain the freedom of action of a deity”. However, he admits that a “god who can create the laws of nature can presumably also circumvent them at will” (p. 142). So he acknowledges at the same time that God is not submitted to any laws, which is a flagrant contradiction in his statements. However, he is unable to recognize this because his reason is impaired by profound hatred against religion.

It is not because God decided something to happen in the future and for this purpose had first to create something else to unfold according to his laws that he had no choice. An engineer who decides to build a car with a precise design has to construct machines that produce individual parts depending on the given dimensions of the car. It would be absurd to claim that he had no choice in the manufacture of these individual parts because they depend on the end product, which is supposed to be a functional car when its parts are assembled. So yes, God had every choice. He chose to create humans without having to improvise or make any compromises and previously determined the conditions under which they would later live. Thereby, the universe had to be extremely fine-tuned (Hawking 1998 p. 129; Ross 2001b p. 31; Jones 2017 pp. 136, 214-215).

In order to explain this fine-tuning, atheists resort to the anthropic principle, of which several formulations are in circulation (Reeves 1995 pp. 216-221; Allègre 2001 pp. 52-53; Barr 2003 pp. 150-167; Jones & Lambourne 2004 pp. 365-366; Krauss 2012 pp. 125-137). According to Hawking (1998 pp. 128-129), the weak anthropic principle assumes that the universe has multiple regions with different configurations. Therefore, if it is sufficiently large or even infinite we should not be surprised that somewhere it contains favorable regions for the evolution of life and humans who wonder about the exceptionality of the universe they live in. The strong version of this principle is the same, except that it supports multiple or an infinite number of universes. So this concept is based on the assumption that life can emerge naturally with some probability greater than zero. However, if life is not a mere biochemical process but if there is flowing some immaterial entity between the molecules, such that only a supernatural being can create it (sec. 1.1.1), then this argument becomes null and void. Even an infinite number of infinite universes, each of which having existed since eternity and containing all possible physical configurations, would be unable to produce life, even in its most primitive form. Such as matter cannot come out of nothing, life cannot emerge from dead matter.

St. Paul states that our knowledge is partial (1 Co 13:9-12), in other words, approximate. This is quite obvious when looking at the history of celestial mechanics: according to the Copernican system, the planets move on perfect circles around the Sun. Kepler slightly corrected this view by showing that two interacting bodies move on ellipses. Newton’s laws allowed a further enhancement by providing the mathematics for the movement of more than two bodies interacting with each other. General relativity takes into account that the interaction of gravity between bodies is not immediate like in Newtonian mechanics but limited by the speed of light. This theory is again only an approximation of reality because it does not take into account what matter is. This is why it can make no predictions when particles come very close together such that other interactions than gravity have to be taken into account, for instance, during the first moments of the big bang. Actually, they try to figure out what happened then by integrating quantum mechanics into gravity. Given the inherent difficulties of this approach, even this is likely to be only an approximation of reality (Fatoorchi 2001 pp. 139-140).

In fact, the known laws of physics break down at time zero: general relativity predicts that at this moment the temperature and density of the universe were infinite. In the case of a closed universe, also its curvature was infinite and its size zero. Such a singularity is regarded with suspicion by most cosmologists (Hawking 1998 p. 138; Ross 2001a p. 170; Jones & Lambourne 2004 p. 362). Moreover, quantum mechanics states that it is impossible to know what happened prior to the Planck-time of 10-43 seconds (Houziaux 1997 p. 35; Jones & Lambourne 2004 pp. 268-269, 362; Jones 2017 p. 217). The string theory offers solutions to these problems but still remains a non-testable hypothesis. Such so-called Theories of everything are indeed based on mere atheist wish-thinking because they violate Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, which prevents cosmologists to fully understand what happened at time zero (Hawking 1998 p. 160; Berg 2001 pp. 96-97; Ross 2001a pp. 123-124; Ross 2001b pp. 190-191; Davis 2002 pp. 34-36; Barr 2003 pp. 279-288; Jones & Lambourne 2004 p. 364-365).

So even though science is in constant progress, it is unable to arrive at a complete understanding of nature. There is not really a “dawn of science” since Galileo and Newton as claimed by Krauss (p. 184). The naive view of the angels pushing the planets was certainly not a milestone in science. But even this view contributed something to science, that is, the awareness that there are planets moving at almost constant speed in contrast to the stars that apparently do not move when observed with the naked eye. Without this awareness the subsequent developments in cosmology could never have taken place because knowledge proceeds by repeated attempts based on trial and error correction. Consequently, if there had never been humans gazing upwards since the Stone Age, asking questions about those luminous points in the sky and making whatever conclusions about them, whether true or not, general relativity would never have been invented and Krauss would not be around to write nonsense in bestselling books.

So physics is the art of simplifying reality. Physical laws are based on human understanding, that is, observation, mathematics, and so on. In other words, they have not been around since eternity. Humans are able to discover them because God created a universe that is approximately understandable for us. Einstein said: “The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible” (Einstein 1954 p. 292). In other words, through laws that can be expressed mathematically, God lets us gain insight into his creation because he wants us to understand his creation and its past in order for us to realize that his words about the universe are correct.

However, physicists have a tendency to confound their laws with reality, whereas they are indeed only approximate models of reality. The first and eternal reality is God, then came the physical reality created by God with the aim to give a host to humans. All the physical laws and properties are subordinated to this purpose. Only after billions of years emerged the models invented by physicists. Now, what to say about those who confound them with reality in order to exclude their Creator?

For atheists like Krauss and Dawkins, a supernatural being is an absurdity, an enemy that must be fought to the bitter end. Such people will never run out of ideas about how to disprove theistic theories. This is why it is better to leave them alone in their corner among themselves where they can forever celebrate the illusion that God does not exist. The Omnipresent has indeed answered their request and prepared for them such a place where he is absent. So they will eventually be where they have always wanted to be and where they will never again be upset by people who contradict them. God wishes them all the best at this place…

Why discuss at all about whether God’s existence can be proven by imperfect physical laws if this is obvious otherwise? We do not depend on whether physicists will one day demonstrate by some theory whether God exists or not. He is not a theory but a living powerful person and thereby can speak for himself. Therefore, he does not need physicists to defend himself. He has manifested his existence in the past, shows it in the present and will reveal it in the future:

‘I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the Lord God, ‘who is and who was and who is to come, the Almighty’ (Rev 1:8).

1.1.5 The Age of the Universe

There are many chronologies that calculate the birth of Adam and the age of the Earth based on the biblical data. All arrive at different dates according to whether the genealogies of the Masoretic text, the Septuagint or the Vulgate are used and from what known historical event one goes back in time (Hughes 1990; Finegan 1998). The probably most popular chronology is the one of Irish archbishop James Ussher (1581-1656) who arrived at 4004 BC for Adam’s birth. This was also considered the age of the Earth since Adam was created only six days later. This date has been indicated in many Bibles translated into English (Ramm 1964 p. 121).

It got first cracks when James Hutton (1726-1797) began to wonder how marine fossils came to be on mountaintops. The answer so far was that Noah’s flood covered the whole Earth, depositing the fossils there. But Hutton argued that slow-acting mechanisms can uplift sea and lake beds over vast periods of time to finally become mountains, which has been confirmed in the second half of the 20th century with the advent of plate tectonic science. Also, Charles Lyell (1797-1875), who is considered to be the father of modern geology, calculated that the Niagara falls were 35’000 years old (Morris 1994 p. 49). This date is somewhat wrong but it nevertheless showed that the Earth is much older than roughly 6000 years (Faure 1986 pp. 1-2; Whorton & Roberts 2008 pp. 174-175, 226).

As a response to Lyell, Philip H. Gosse (1810-1888) published his book entitled Omphalos, which is the Greek word for navel. He chose this title because in his view Adam must have had a navel. But at the same time he also thought that Adam has been directly created by God, so without having grown inside a woman’s womb and being linked to her by an umbilical cord. Adam’s navel would show that God created the world with the appearance of prehistory and thereby with age, even though everything was brand-new. Gosse was heavily criticized for this proposal, arguing that he would turn God into a deceiver (Whorton & Roberts 2008 p. 175; Dembski 2009 pp. 64-65).

By the late 19th century, the prevalent view – even among the most conservative Christians – was indeed that the Bible allowed for an ancient Earth (Numbers 2006 p. 7). In fact, various proposals have been put forward to overcome the conflict due to the incompatibility between the age of the Earth provided by the Bible and science. William H. Green (1890), for example, argued that the genealogies of Genesis were not strict father-son relationships but included large gaps such that it is indeed impossible to determine the precise age of the human species. So an ancient origin of 500’000 BC or more would pose no theological difficulties (Nicole 1980 pp. 141-142).

Another proposal involving only one gap, the gap theory, conjectured that God originally created a perfect world (Gen 1:1), which was first ruled by Lucifer before his fall. But thereafter, he caused a tohu wabohu (Gen 1:2), that is, death and chaos upon the earth for millions of years, during which the various geological formations and the fossil record took place. God then restored the original world in six literal creation days. This strange theory was widespread at this time but no longer has many supporters (Ramm 1964 pp. 135-136; Blocher 1984 p. 41; Ross 2001b pp. 23-24; Whorton & Roberts 2008 p. 91-92; Walton 2009 p. 112).

As long as one believed that the first humans were created only shortly after the formation of the Earth, such theories were sufficient. But when it became clear that the Earth and the universe was not millions but billions of years old, they needed an enhancement. One of them was the view that the creation days are long periods of time, which has been called the age-day theory (Ramm 1964 p. 145). However, this view already had adherents in the first centuries AD because the Sun, Moon and stars were only created on the fourth day (Gen 1:14-19). So the argument is that when God created the light and separated it from the night on the first day (Gen 1:3-5), this did not involve the light of the Sun. Thereby, a creation day does not last 24 hours but has an undetermined length of time (Whorton & Roberts 2008 pp. 173-174). This is supported by the fact that not even the planet Earth has been created on the first day, as discussed in section 1.1.1. So even Earth’s 24-hour rotation was absent then.

Together with the antiquity of the Earth, also evolutionary ideas began to spread since Darwin’s publication of On the Origin of Species (1859), which prompted amateur geologist and Seventh-Day Adventist George McCready Price to publish his book The New Geology (1923) in an attempt to counter-attack those views, which in his eyes were contrary to the teaching of the Bible. Outside of his own church, Price had little support. But his ideas became discovered by John C. Whitcomb and Henry M. Morris, who wrote the bestseller The Genesis Flood (1961) as an answer to Bernard L. Ramm’s well-received Christian View of Science and Scripture (1954), which was an attempt to reconcile Genesis with science. Their book laid the foundation for creation science and young-earth creationism (Blocher 1984; Ross 2001b p. 87; Whorton & Roberts 2008 p. 176).

As the name implies, the main concern of young-earth creationists (YECs) is what they conceive as the incompatibility of a six-day creation with a billion-year-old universe (Morris 1994 p. 122). As already outlined above, this is not a real issue. Furthermore, as unbelievable as this may sound, the date of the big bang, our galaxy and the solar system as well as major steps in human evolution can be retrieved from the patriarchs’ ages by simple recurring mathematical methods , as we shall see in chapter 3.3. But YECs also see a problem with the fact that death was already around billions of years before Adam’s fall. This is a real issue worth being addressed (Numbers 2006 p. 7; Dembski 2009 pp. 48-49). It will be done in chapter 2.4.

On the other hand, it’s beyond the scope of this book to go into detail about why YECs are wrong in opposing the overwhelming evidence from all sorts of scientific fields for an old Earth. There are many good books out there that do this thoroughly (e.g., Ramm 1964 ch. VI; Whorton & Roberts 2008 ch. 20; Newman et al. 2007 ch. 1; Bonnette 2014 pp. 184-191). I would just like to add, taking the risk that this also has already been said, that YECs are co-responsible for the rise of atheism by refusing to accept irrefutable scientific facts. It is because of them that Dawkins can snootily – but with some justification – say that religious people are extremely easy to handle, in the sense that their arguments can easily be refuted, thus drawing especially young people into atheism. So YECs render no service to religion, in the contrary.

God wants us to scrutinize nature in order to discover him through it (Wis 13:1-9; Rom 1:20). So if nature tells us that it is billions of years old, we should take it seriously. God is no deceiver! He certainly did not create a nature that leads us to wrong conclusions when using our God-given reason capable of investigating nature. A newborn does not start with studying the Bible but first discovers his/her physical environment in order to understand empirically its functioning and build trust in it. Only later will he/she be able to read and evaluate a written description on its veracity by comparing its content with what he/she learned first, to come to the conclusion that descriptions can be correct or erroneous or interpreted falsely. So what we trust in the first place is what we perceive with our senses and what we can infer from what we observe, even though this is also subject to error, of course. However, as far as the age of the universe is concerned, there is no doubt about it from a scientific point of view.

1.1.6 Rules

For the correct understanding of the rest of the first chapter of Genesis, we must apply the same rules of interpretation used for the first verse. So let us resume these rules:

- We have seen that the planet Earth formed billions of years after the big bang. This is why a literal interpretation linking the Hebrew words shamayim (heaven) and erets (earth) in Genesis 1:1 to our planet implies an apparent anachronism because the Earth and its atmosphere were not created in the beginning. This oddity points to what will be called vertical chronology, which refers to several objects bound by analogy and steps over several stages of the horizontal chronology, which passes from one stage to the next closest. It is solved by reframing the context to the main object. In the case of Genesis 1:1, this is the spiritual world of the angels. Such anachronisms through literal interpretation occur several times and are always solved in this manner.

- We have also seen that there is some time between the creation of shamayim and erets: the invisible world was indeed created before the physical universe. So it is not an instantaneous creation of both entities, contrarily to what the word and between them may suggest. The same is true for the rest of the account and one has to determine from the context when large time intervals occur.

- The couple shamayim and erets are terms that at each repetition form a new duality referring to several contexts: at first, it applies to the invisible and visible word. Then, within the visible world, it means space-time and matter. The same reframing happens for other levels up to the couple atmosphere / planet Earth (fig. 3). These multiple references involve restrictions because the considered context of the creation story becomes increasingly limited in space and time by heading to the creation of man.

References

- Allègre, C. (2001). Introduction à une Histoire naturelle (éd. 2nd). Paris: Fayard.

- Aquilina, M. (2006). Angels of God : the Bible, the Church, and the Heavenly Hosts. Cincinnati: Servant Books.

- Barr, S. M. (2003). Modern physics and ancient faith. University of Notre Dame Press.

- Berman, M. S. (2009). On the Zero-Energy Universe. International Journal of theoretical Physics, 48(11), 3278-3286.

- Billet, B., Alonso, J.-M., Bobrinskoy, B., Oraison, M., & Laurentin, R. (1973). Vrai et fausses apparitions dans l'Église(2nd ed.). P. Lethielleux - Bellarmin.

- Blocher, H. (1984). In the Beginning: the Opening Chapters of Genesis. (D. G. Preston, Trans.) Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press.

- Bond, H. E., Nelan, E. P., VandenBerg, D. A., Schaefer, G. H., & Harmer, D. (2013). HD 140283: A star in the solar neighborhood that formed shortly after the Big Bang. The AstrophysicalJournal Letters, 765(1), L12.

- Bonnette, D. (2014). Origin of the Human Species (3rd ed.). Ave Maria: Sapientia Press.

- Claeys, C. (1987). Die Bibel bestätigt das Weltbild der Wissenschaft. Stein am Rhein: Christiana-Verlag.

- Colin-Simard, A. (1981). Les apparitions de la Vierge: leur histoire. Fayard/Marne.

- Davis, J. J. (2002). The Frontiers of Science and Faith: Examining Questions from the Big Bang to the End of the Universe. Downers Grove: lnterVarsity Press.

- Dembski, W. (2009). The End of Christianity: Finding a Good God in a Evil World. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group.

- Denzinger, H. (1955). The Sources of Catholic Dogma (13th ed.). (R. J. Deferrari, Trans.) Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications.

- Einstein, A. (1954). Ideas and Opinions. (S. Bargmann, Trans.) New York: Crown.

- Fatoorchi, P. (2001). A Brief Note on the Problem of the Beginning: From the Modern Cosmology and “Transcendental Hikmah” Perspectives. In R. L. Herrmann (Ed.), Expanding Humanity’s Vision of God: New Thoughts on Science and Religion. West Conshohocken: Templeton Foundation Press.

- Faure, G. (1986). Principles of Isotope Geology (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Finegan, J. (1998). Handbook of Biblical Chronology: Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible (2nd ed.). Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc.

- Hartle, J. (2003). Gravity: An Introduction to Einstein's General Relativity. Addison Wesley.

- Hawking, S. (1998). A Brief History of Time (10th ed.). Bantam Books.

- Höfer, J., & Rahner, K. (Eds.). (1957). Lexikon für theologie und Kirche (2nd ed.). Freiburg im Breisgau: Verlag Herder.

- Houziaux, A. (1997). Le tohu-bohu, le serpent et le bon Dieu. Paris: Presses de la Renaissance.

- Hughes, J. (1990). Secrets of the Times: Myth and History in Biblical Chronology. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

- Jones, M. H., & Lambourne, R. J. (Eds.). (2004). An Introduction to Galaxies and Cosmology. Cambridge University Press.

- Jones, B. (2017). Precision Cosmology: the First Half Million Years. Cambridge University Press.

- Joyeux, H., & Laurentin, R. (1985). Études médicales et scientifiques sur les apparitions de Medjugorje.Paris: O.E.I.L.

- Kramer, S. N. (1981). History Begins at Sumer (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Krauss, L. (2012). A Universe from Nothing. New York: Free Press.

- Kreeft, P. J. (1995). Angels and Demons: What Do We Really Know about them? San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- Melia, F. (2022). Initial Energy of a Spatially Flat Universe: A Hint of its Possible Origin. Astronomische Nachrichten, 343(3), e224010.

- Morris, J. D. (1994). The Young Earth. Green Forest: Master Books.

- Newman, R., Phillips, P., Eckelmann, H., Snow, R., Green, W., & Wonderly, D. (2007). Genesis One and the Origin of the Earth (2nd ed.). Interdisciplinary Biblical Research Institute.

- Nicole, R. R., & Michaels, J. (Eds.). (1980). Inerrancy and Common Sense. Grand Rapids: Baker Book House Company.

- Numbers, R. L. (2006). The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press.

- Parente, P. P. (1994). The Angels: In Catholic Teaching and Tradition. Charlotte: TAN Books.

- Ramm, B. (1964). The Christian View of Science and Scripture. The Paternoster Press.

- Reeves, H. (1988). Patience dans l'Azur: L'évolution cosmique. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Reeves, H. (1995). Dernières nouvelles du cosmos: la première seconde (Vol. 2). Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Ross, H. (2001a). The Creator and the Cosmos : How the Greatest Scientific Discoveries of the Century Reveal God (3rd ed.). Colorado Springs: NavPress.

- Ross, H. (2001b). The Genesis Question: Scientific Advances and the Accuracy of Genesis (2nd ed.). Colorado Springs: NavPress.

- Ross, H. (2008). Why the Universe is the Way it is. Grand Rapids: Baker Books.

- Schönborn, C. (2007). Chance or Purpose?: Creation, Evolution, and a Rational Faith. (H. Taylor, Trans.) San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- Sharratt, M. (1996). Galileo: Decisive Innovator. Cambridge University Press.

- Tryon, E. P. (1973). Is the universe a vacuum fluctuation? Nature, 246(5433), 396-397.

- Walton, J. H. (2009). The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press.

- Whorton, M., & Roberts, H. (2008). Holman QuickSource Guide to Understanding Creation. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group.

This site is hosted by Byethost

Copyright © Vierge Press

| < | > |