3.1 An Early and Late Flood

Abstract

Before asking questions about the historical accuracy of the flood account, we will first examine its traditional interpretation and show that it is indeed a multilayered account. This will allow us to go beyond the literal meaning referring to the local inundation that occurred about 2500 BC in Mesopotamia, the late flood, and show us that there was also an earlier deluge around 7500 BC.

Contents

Theology

The Flood Cycle

Dating the Flood

Global or Local Flood?

Early Flood Scenarios

References

Site Navigation

3.1.1 Theology

Just as there is a parallel between Adam and Jesus, there is also one between Noah and Jesus. But unlike Adam, who by his disobedience is rather an antitype of Jesus, Noah by his obedience is a prototype of Christ because he did all what God told him to do and built the ark (Gen 6:9; 6:22; 7:5; Heb 11:7), thus exposing himself to the ridicule of his contemporaries who were disobedient (1 Pe 3:20). Even though this mockery is not explicit in Scripture, it can be inferred (Holzer 1964 p. 240) and prefigures Christ being mocked by Roman soldiers and other people (Mt 27:28-31; Mk 15:29-32).

The water of the flood is also an element that points to Jesus’ time. It foreshadows baptism, which washes away sin (1 Pt 3:21). So the flood must be understood in the same sense, that is, as an act of purification from sin: it delivered the world from the godless in order to save it. This parallel contradicts the image of many people who see God as a capricious, angry and selfish being who feels hurt in his pride by those who dare to question him and therefore are punished. Quite on the contrary, he is a Savior who sent the flood not in order to destroy mankind but to prevent it from self-destruction (Holzer 1964 pp. 239-240; Martelet 1976 p. 23; Blocher 1984 p. 208).

Another prophetic element is the ark. The Hebrew word tebah used for it means box and only occurs a second time in Exodus 2:3-5, where it designs the basket in which baby Moses was led and released to the waters of the Nile (Zeilinger 1986 p. 112). The basket was constructed with a wood-like material (papyrus) and made waterproof with bitumen (Gen 6:14; Ex 2:3) like Noah’s ark. Its purpose was to save Moses from Pharaoh’s persecution of the Hebrew people (Ex 1:8-22). So the waters here play a similar role than in Noah’s time. They secure the life of the one who will later lead Israel out of Pharaoh’s oppression with the help of God who sent ten plagues over Egypt, of which the most important was the drowning of its army by the waters of the Red Sea (Ex 7-14). Thereby, Moses manifestly played an analogous role than Noah.

The ark of Noah also prefigures the ark of the covenant, which was made likewise of wood and covered inside as well as outside, not with bitumen, but with gold. For both arks exact instructions were given how to construct them (Gen 6:14-16; Ex 25:10-11). However, the most striking parallel can be drawn from the contents of both arks, which needs a brief detour.

The Law of Moses was only fulfilled by Christ (Mat 5:17-18; Rom 13:8-10; Heb 3-10). Thereby, the old covenant is merely a prefiguration of the new covenant. This is evidenced, for instance, by the tablets of stone on which were written the ten commandments given to Moses on Mount Sinai (Ex 32-34). So they were written outside man. This changed with Jesus, who is the Messiah fulfilling the Law, which was henceforth written by the Holy Spirit into the hearts of flesh of all those who follow Jesus, in other words, inside man (Dt 6:4-8; Jer 31:33; 2 Co 3:3). This is why Israel was unable to accomplish the Law and thus repeatedly caused God’s anger (Mt 23:4; Ac 15:10; Gal 5:1).

Now, Jesus came into the world through Mary, who protected him within herself, just as the ark of the covenant served as a protecting envelope for the stone tablets (Ex 25:16; 31:18; 40:20; Dt 10:1-5) and the basket of Moses as well as the ark of Noah saved the righteous ones inside them. So all three arks can be regarded as prototypes of Mary (Scheeben 1946 p. 39; Martelet 1976 pp. 27-31; Laurentin 1982 pp. 59-75). By the way, the Church housing the Eucharist is likewise such an envelope just like the Jerusalem temple, which served as a shrine for the ark of the covenant with its tablets inside.

These few examples show that the flood, seen from its present, points to the future, in particular to the final days. It is Jesus himself who suggests this:

As it was in the days of Noah, so will it be in the days of the Son of man. They ate, they drank, they were given in marriage, until the day when Noah entered the ark, and the flood came and destroyed them all. [...] So will it be on the day when the Son of man is revealed (Lk 17:26-30).

The day of the Son of man means the glorious return of Christ. In the book of Revelation, these days are depicted as a judgment against the city of Babylon, which is a timeless synonym for any society at the height of its decadence at the example of the civilization that constructed the tower of Babel and later exiled the Jews under the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar. In the historical context of Revelation, Babylon is applied to Rome and its depraved emperors, which underlines its timelessness (Bauckham 1993 p. 130).

This is why Babylon can also be applied to the end of the world because it is then when the decadence on earth will culminate. Isaiah, for example, writes concerning this future Babylon:

Wail, for the day of the Lord is near, as destruction from the Almighty it will come. Therefore all hands will be feeble, and every man’s heart will melt, and they will be dismayed. Pangs and agony will seize them, they will be in anguish like a woman in travail. They will look aghast at one another, their faces will be aflame (Isa 13:8).

And elsewhere:

For behold, the Lord will come in fire, and his chariots like the stormwind, to render his anger in fury, and his rebuke with flames of fire (Isa 66:15).

The book of Revelation is also evoking fire: the ten apocalyptic kings will “devour the flesh” of Babylon, the prostitute, “and burn her up with fire, for God has put into their hearts to carry out his purpose” (Rev 17:12-18). This is often attributed to nuclear mass destruction during a third World War. However, such an interpretation does not align with God’s intention to “destroy those destroying the earth” (Rev 11:18), which shows that God wants to prevent the Earth from being destroyed. Furthermore, it is unlikely that Christ will return to a radioactively contaminated or otherwise irreversibly polluted Earth and reign on it for a thousand years (Rev 19:11-20:6).

There are some Saints who think that human history is unfolding in three ages according to the Holy Trinity, each of which ending with a deluge: the reign of the Father ended with Noah’s flood and the reign of the Son with the effusion of Jesus’ blood. Since then, we are in the reign of the Spirit, which will end with a deluge of fire, love and justice (Armbruster et al. 1986 pp. 149-153). This agrees with what has been discussed previously, namely that the flood prefigures baptism, which has been introduced by John, who said that while he was sent to baptize with water, Jesus will baptize with the Holy Spirit (Jn 1:33). A similar baptism of fire already took place at Pentecost after Ascension, when the Holy Spirit descended on Jesus’s disciples like fire, while being mocked by some observers like in Noah’s times. St. Peter states that this will happen again at the end of times on a global scale (Ac 2:1-21).

Isahia predicts that mankind will become “rarer than fine gold” (Isa 13:12). This precious metal has not always a positive connotation in the Bible, but sometimes its resistance to fire is used as an image for faith resisting the fire of the end times (1 Pe 1:7; Rev 3:17-18). So those who have faith have a heart of gold, which will melt in love for God at the end-time encounter with him. But those who are indifferent to God or always question him and want to know everything better than him have a heart of stone that will not melt but break apart in the fire. The faithful will find refuge in the Church as the mystical body of Christ, serving as an ark of Noah (Denzinger 1955 nos. 468, 1647), which will spiritually shelter people of all colors and nations from around the world like the species that were gathered in the ark from everywhere on earth (Gen 6:20).

God established a covenant with Noah, promising to never again destroy the Earth and its inhabitants with the waters of a flood (Gen 9:9-11). How can this be reconciled with an eschatological global deluge of fire? One could argue that the accent is over the waters, in other words, that God will not judge the world again in the same way “as I have done” (Gen 8:21). Thereby, judging it with fire does not break God’s promise. This is certainly not untrue.

However, Bauckham (1993 pp. 51-53) proposes a more subtle solution. He first mentions Ezekiel 1:28 and Revelation 4:3, where there is mention of a rainbow in the description of God’s splendor, which he takes as an allusion to the covenant with Noah symbolized by a rainbow (Gen 9:11-17). A rainbow indeed forms when the Sun is not far above the horizon and shines rather horizontally into a region of raindrops, which reflect and refract the white light into its spectrum. This implies that the cloud layer has openings, inaugurating the end of the flood and symbolizing light and hope at the end of the tunnel. So this symbol of the new covenant is quite adequately chosen.

Furthermore, since the Sun is in the back of the observer of a rainbow, perhaps even hidden by a mountain, Martelet (1976 pp. 23-24) even sees a symbol of the Virgin Mary in the rainbow because she reflects the light of Christ even if he is invisible. As discussed in section 2.3.3, the Moon is an image of Mary just as the Sun is an image of Christ. And the Moon indeed reflects the light of the Sun in the night when it is hidden. So this comparison makes sense.

Bauckham then argues that in Revelation 11:18 there is another allusion to the flood story by mentioning God’s plan to destroy those who destroy the Earth (Gen 6:13). So this punishment matches the sin that provoked it (Cassuto 1964 p. 57), just as in Revelation 16:6; 18:6; 22:18-19. The Greek verb diaphtheiro, which can mean both destroy and corrupt, is used. The destroyers of the earth are the powers of evil: the dragon, the beast, and the harlot of Babylon, who with their violence, oppression and idolatrous religion are ruining God’s creation. His faithfulness to his creation requires that he destroy them in order to preserve and to deliver the earth from evil.

In Genesis 6:11-13, 17 there is a similar wordplay with the Hebrew verb sahat, which also can mean both to destroy and corrupt. Here again, God destroys with the flood, along with the Earth itself, those who are corrupting the Earth with their evil ways, thus delivering God’s creation from the ruinous violence of its inhabitants. So there is apparently a parallel between the Noahic flood and the end-time judgment. But, if true, it seems to contradict the covenant with Noah, which consists of God’s promise to never again destroy the earth by a flood, because a similar judgment would happen once more at the end times.

In order to solve this contradiction, Bauckham argues that the waters of the flood are the primeval waters of chaos (Gen 1:2; 7:11), a destructive potential threatening the universe with reversion to chaos. During the flood, God indeed returned the world to chaos, a view held by other authors (Clines 1972; Blocher 1984 p. 206), in the sense that the initial creation of the Earth by separation into high and low waters (sec. 1.4.2) was undone by removing this separation. Thus, the world that was created out of water was again returned to water (2 Pet 3:5-6). Genesis 7:11 indeed reports that not only heaven’s windows were opened but also the fountains of the deep burst forth. The waters of chaos are the sea from which the beast arises (Rev 13:1; Dan 7:2-3), which sets an analogy between them. The destruction of the devil, death and Hades (Rev 20:10, 14) also lead to the removal of the sea (Rev 21:1), which further confirms this analogy. In other words, the waters of chaos are finally no more.

So according to Bauckham the end-time judgment, which leads to the inauguration of a new earth, is not a second flood but, on the contrary, the final removal of the threat of another flood, making God’s creation eternally secure from any threat of destructive evil. Thereby, God is not only faithful to the Noahic covenant but indeed surpasses it by taking his creation beyond the threat of evil. Afterwards, it becomes the home God indwells with the splendor of his divine glory (Rev 21:3, 22, 23).

3.1.2 The Flood Cycle

Just as Jesus is the ultimate new Adam, Noah holds an intermediate and prefigurative step in this direction, which is why he is also involved in a cycle of four typical phases like Adam (ch. 2.2). This cycle is described in Genesis 4-11 centered around its punishment phase: the flood. However, just as there were several paradises, there were as many floods at different times, each one representing a cycle, as we are going to see. In other words, the flood narrative can be interpreted in different ways, each of which being a valid solution.

First, we need to localize the four phases in the account. The peace of the first phase starts with the offspring of Adam and Eve (Gen 4:1-2), which initiates their return to peace (sec. 2.3.3). So this peace is a transition from the personal cycle of our ancestors to the first phase of the flood cycle that encompasses a certain population of this time. This first phase is not perfect since it takes place outside Eden, but it is relatively peaceful compared to the other phases.

In the beginning of this phase, Cain indeed murdered his brother Abel such that God cursed him to be “a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth” (Gen 4:8-12). Cain complained to God about this fate, which is why he was granted to avenge himself sevenfold if an aggressor should harm him (Gen 4:13-15). This cannot be considered a peaceful context. However, the mark God put on Cain prevented violence by dissuasion through the threat of revenge, whatever this mark may have been. Therefore, this time can nevertheless be considered as belonging to a relatively peaceful first phase. However, it passed gradually into the phase of sin characterized by a steady increase of violence.

In fact, five generations later a man named Lamech emerges from Cain’s descent. He killed a young man for having wounded him, boasting that he no longer would revenge himself sevenfold like Cain but seventy-sevenfold (Gen 4:17-24). So here we see a surge in violence. Apparently, the dissuasion has become ineffective, such that the revenge is executed and even multiplied. The age of seven hundred and seventy-seven years attributed to another Lamech – Noah’s father – is certainly a hidden allusion to the growth of violence within all the antediluvian society, even though there is no mention of this Lamech being violent (Gen 5:28-31).

This stands in opposition to the teaching Jesus gave to St. Peter some millennia later: “I do not say to you [to forgive] seven times, but seventy-seven times” (Mt 18:22). So instead of forgiveness, a spiral of vengeance was set in motion until the flood (Zeilinger 1986 p. 104), when God

saw that the wickedness of man was great on earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually (Gen 6:5).

He regretted and grieved him to his heart that he had made man on earth, and decided:

I will blot out man whom I have created from the face of the ground, man and beast and creeping things and birds of the heaven, for I am sorry that I have made them (Gen 6:6-7).

The survival of Noah, his family, and the animal species he took on board his ark belongs to the corresponding revival phase, which initiated a second creation because all inhabitants on earth have perished according to a literal reading. Thus Noah became a new ancestor for a renascent humanity. This is why he and his sons received from God a benediction of fertility (Gen 9:1) similar to that already given to Adam and Eve (Gen 1:28).

The revival also comprised a relief in the workload, which equally derived from Noah (Gen 5:29), and may be a hint at the establishment of governmental structures, the specialization of the different labors and therefore their rationalization. In any case, the following account on the construction of the tower of Babel mentions the birth of a civilization (Gen 11:1-9), which are profitable for everybody compared to hunter-gatherer societies and therefore contribute to everyone’s welfare.

3.1.3 Dating the Flood

The date of the flood must be calculated by going back in time from a known historical event, using the data supplied by the Bible like the patriarchs’ ages and others. The construction date of Solomon’s temple in 968/967 BC is often used for this purpose, even though certain authors claim that this first temple of the Jews never existed (Finkelstein & Silberman 2001 p. 128). These are archaeologists of the minimalist school who reject all for which there is no overwhelming evidence (Hoffmeier 1997 p. viii). However, it is not possible to turn over every stone, so such distrust is misplaced. The construction date of the first temple has indeed been thoroughly calculated by Edwin R. Thiele by comparing biblical and extra-biblical sources. He found out that there were coregencies and overlapping reigns of Hebrew kings. His system is widely accepted as the basic work on the subject (Finegan 1998 pp. 246-249).

1 Kings 6:1 states that Solomon’s temple was built 480 years after the Exodus. This is still disputable because the books of Judges and Samuel seem to indicate a longer time span of almost 600 years: following Hughes (1990 p. 61), Israel wandered in the desert for 40 years after the Exodus (Num 14:33) and took about 5 years for the conquest of Canaan. Thereafter, a period of 450 years elapsed until Judge Eli. The time during which Samuel and Saul ruled over Israel is not known from biblical sources, even though Acts 13:21 states 40 years for Saul’s reign. Historiographer Flavius Josephus indicates about 52 years for both (Hughes p. 270). David reigned 40 years over Israel (1 Kings 2:11) and the construction of the temple started in the 4th year of Solomon (1 Kings 6:1). So this yields 591 instead of 480 years. It is possible that this discrepancy is also due to overlapping periods during which Judges ruled over Israel. Contrarily to the Kingdom, though, extra-biblical sources of the era of the Judges are rare, making a verification of such a claim difficult.

Assuming that 1 Kings 6:1 is correct, this would place the Exodus to 967 BC + 480 = 1447 BC. Scholars are divided about this date. Some claim that it fits well with Egypt’s archaeological and historical record, others disagree and prefer to place it in the 13th century BC, still others think that the Exodus did not happen at all (Free & Vos 1992 pp. 87-89; Price 1997 pp. 125-140; Finegan 1998 pp. 202-232; Fischer 2008 p. 99; Keller 2015 p. 114).

The sojourn of Israel in Egypt is another point of contention. Exodus 12:40 indicates 430 years. However, St. Paul states that the Mosaic law was introduced 430 years after God’s promise to Abraham (Gal 3:16-17). Israel arrived in the wilderness of Sinai three months after the Exodus (Ex 19:1). In the same region, on Mount Sinai, Moses received the tablets of stone with the ten commandments written on them (Ex 31:18), so shortly after the Exodus. If the introduction of the law is considered this event, then the 430 years started a bit earlier according to St. Paul, which would shorten the stay in Egypt and postpone the dates dependent on it to later times. Still another interpretation is found in the Septuagint, which claims that “The time that the people of Israel dwelt in Egypt and in the land of Canaan was four hundred and thirty years”. The Masoretic text, though, does not mention Canaan in this context (Hughes 1990 p. 258; Finegan 1998 p. 204).

Israel was born with Jacob’s twelve sons, from whom the twelve tribes descended. They arrived in Egypt with their father Jacob, who was 130 years old at this moment (Gen 47:9). So this is when the stay of 430 years in Egypt commenced, while it ended in 1447 BC with the Exodus. Let’s thereby assume that Jacob was born around 1447 BC + 430 + 130 = 2007 BC. Abraham was 100 when Isaac was born (Gen 21:5) and Isaac 60 when Jacob was born (Gen 25:26), so Abraham was 160 years old at Jacob’s birth. This is why Abraham was born around 2007 BC + 160 = 2167BC. However, because of the uncertainties regarding the dates of the temple, the Exodus and the stay in Egypt, there are a lot of other chronologies that yield other dates, the most prominent being the Ussher chronology (Hughes 1990; Finegan 1998).

From 2167 BC one can retreat in time using the genealogies in Genesis 5 and 11 (tab. 5). Contrarily to the previous calculation, however, we want to do this accurately based on the Masoretic text. Assuming that the Hebrew verb yalad used in the genealogies means to father (even though it can also mean to bear as in Genesis 25:26), we have to add the nine months of pregnancy between the conception and birth for each patriarch. One may wonder if such accuracy makes any sense, given the fact that we even don’t exactly know at what month and day during the indicated year the patriarchs were born. But since this information is not available, we are supposed to understand that the full years of the conceptions are the correct dates to be taken into account. The reason why this is necessary will become clear in chapter 3.3.

Patriarch |

Age at fathering of next patriarch |

Age at birth of next patriarch |

Years from Adam’s birth to next patriarch (rounded) |

Age |

Birth by adding the ages from Adam to Terah |

Genesis |

Adam |

130 |

130.75 |

0 |

930 |

0 |

5:3-5 |

Seth |

105 |

105.75 |

131 |

912 |

930 |

5:6-8 |

Enosh |

90 |

90.75 |

237 |

905 |

1842 |

5:9-11 |

Kenan |

70 |

70.75 |

327 |

910 |

2747 |

5:12-14 |

Mahalalel |

65 |

65.75 |

398 |

895 |

3657 |

5:15-17 |

Jared |

162 |

162.75 |

464 |

962 |

4552 |

5:18-20 |

Enoch |

65 |

65.75 |

627 |

365 |

5514 |

5:21-24 |

Methuselah |

187 |

187.75 |

692 |

969 |

5879 |

5:25-27 |

Lamech |

182 |

182.75 |

880 |

777 |

6848 |

5:28-31 |

Noah |

501.51 |

502.26 |

1063 |

950 |

7625 |

5:32; 9:28 |

Shem |

100 |

100.75 |

1565 |

600 |

8575 |

11:10-11 |

Arpachshad |

35 |

35.75 |

1666 |

438 |

9175 |

11:12-13 |

Shelah |

30 |

30.75 |

1702 |

433 |

9613 |

11:14-15 |

Eber |

34 |

34.75 |

1732 |

464 |

10046 |

11:16-17 |

Peleg |

30 |

30.75 |

1767 |

239 |

10510 |

11:18-19 |

Reu |

32 |

32.75 |

1798 |

239 |

10749 |

11:20-21 |

Serug |

30 |

30.75 |

1831 |

230 |

10988 |

11:22-23 |

Nahor |

29 |

29.75 |

1861 |

148 |

11218 |

11:24-25 |

Terah |

129.25 |

130 |

1891 |

205 |

11366 |

11:26-12:4 |

Abram |

100 |

100.75 |

2021 |

175 |

11571 |

21:5; 25:7 |

Table 5: Chronology of the patriarchs allowing the calculation of several floods.

There are two exceptions to this rule. In table 5, Noah is indeed given an age of 501.51 years when he fathered Shem, Ham and Japheth, even though Genesis 5:32 states that he was 500 years old when he fathered them, suggesting that they were triplets. However, this cannot be the case for the following reasons: the flood began “in the 600th year of Noah’s life, in the 2nd month, on the 17th day of the month” (Gen 7:11). This means that Noah still had not yet achieved his 600th year. So he was exactly 599 years, 2 months and 17 days old at the beginning of the flood, which lasted 370 days (tab. 6), in other words, a year and 16 days, taking 354 days for a Jewish year (Finegan 1998 p. 31). Adding this period to Noah’s age when the flood began yields his age of 600 years, 3 months and 4 days when the flood ended, taking 29 days for a Jewish month based on the moon cycle (Finegan 1998 p. 31).

Now, Shem was 100 years old 2 years after the flood when he fathered Arpachshad (Gen 11:10). So Noah’s age at this moment was 602 years, 3 months and 4 days. And he was 100 years younger when Shem was born, that is, 502 years, 3 months and 4 days old, or about 502.26 years. Taking into account a pregnancy of 9 months yields Noah’s age at his fathering of Shem: 501 years, 6 months and 4 days, or about 501.51 years. This age does not stand in contradiction with Genesis 5:32 but just shows that Noah’s tree sons were born one after another, Shem simply not being the first-born.

Also Terah fathered three sons – when he was 70 years old (Gen 11:26). Assuming again that they were no triplets and Abraham was not the eldest, Terah’s age at Abraham’s birth can be calculated as follows: according to Acts 7:4, God called Abraham to leave Haran after Terah died there at the age of 205 years (Gen 11:32). Let’s assume that Abraham left Haran immediately after his father’s death. Let then x be Terah’s age at Abraham’s birth and y Terah’s postmortem age when Abraham left Haran, that is, y = 205. Since Abraham left Haran at the age of 75 years (Gen 12:1-4), we have 75 = y – x or x = y – 75 = 130. This is why Terah must have been 130 years old at the birth of Abraham (Allis 1943 p. 262), so he fathered him at the age of 129.25 years instead of 70 years. Consequently, we have here a similar situation to the birth of the three sons of Noah: they were born one after another, but the eldest is not Abraham although mentioned the first. In addition, Noah is the 10th patriarch after Adam, just as Terah is the 10th after Noah.

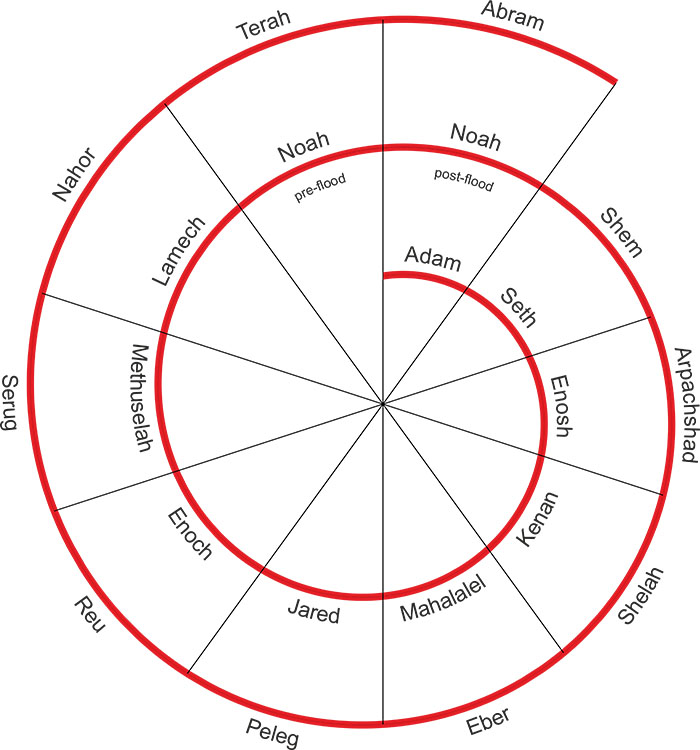

This connection between Noah and Terah can be expressed graphically if all patriarchs are lined up along a spiral (fig. 12) and if one divides Noah’s life into the time before and after the flood. This has to be done because Noah is kind of a new Adam, with whom humanity starts again from scratch. This obviously does not begin at Noah’s birth but only after the flood. Noah received indeed a similar benediction of fertility (Gen 9:1) than Adam (Gen 2:28). This way, also Abram is connected with Adam and Noah, all of whom are indeed the ancestors of new peoples. The spiral also suggests that history repeats itself and cycles through time, which can happen more than once. This will be deepened further on.

Figure 12: When the patriarchs are aligned along a spiral, connections between Adam, Noah, Terah and Abram are revealed. It shows in particular that Adam prefigures Abram (or Abraham) as the first patriarch of a new era.

So according to the patriarchs' ages indicated in Genesis 5 and 11:10-26, about 2021 years elapsed from Adam’s to Abraham’s birth in 2167 BC, taking into account the time of pregnancy (tab. 5). Therefore, Adam must have been born around 2167 BC + 2021 = 4188BC. The time from Noah’s to Abraham’s birth is about 958 years. When the flood arrived, Noah was 600 years old (Gen 7:6). Therefore, 358 years passed from the flood to Abraham’s birth in 2167 BC. The flood of Noah consequently took place in 2167 BC + 358 = 2525BC. This flood date is subject to the same uncertainty as that of Abraham’s date of birth. By the way, young-earth creationists arrive at about the same date (Dembski 2009 p. 62).

3.1.4 Global or Local Flood?

A global flood that wiped out all life on earth around 2500 BC is so overwhelmingly absurd that I don’t consider it necessary to present the arguments against it. There is a vast literature about this topic (e.g., Ramm 1964 pp. 156-169; Hill 2002). Young-earth creationists nevertheless stick to a global flood because they postulate that the Bible has more authority than science (Whitcomb & Morris 1961; Morris 1974 pp. 103-129). Some go even as far as to make a distinction between Christians and non-Christians upon their opinion whether the flood was global or not (Ross 2001b p. 145).

A revealed truth is certainly above human knowledge. But if a superficial literal reading of the flood story leads to obvious contradictions, our God-gifted reason should not ignore them. Instead, one should consider apparent contradictions as open invitations to dig deeper. In other words, the premise should be that God’s words are exempt of any contradictions instead of blindly believe in them, which is not the same. For in the event that apparent contradictions appear in God’s words, we should then conclude that there is something we don’t understand, humbly remaining open to a better understanding in the near or far future instead of proudly and resoundingly equate nonsense with absolute truth.

So the flood occurring at 2500 BC was certainly a local event (Ramm 1964 pp. 162-169; Ross 2001b pp. 145-161; Fischer 2008 pp. 69-73; Whorton & Roberts 2008 pp. 155-163). Many flood scenarios have been proposed for local floods. For instance, the sea-level rise after the last glaciation, affecting the coasts of the whole planet (Ramm 1964 p. 159; Keller 2015 p. 23), and the Black Sea deluge (Ryan & Pitman 1998). There are indeed flood stories from all over the world, which some interpret as proof for the same worldwide catastrophe (Keller 2015 p. 22; Van Schaik & Michel 2016 p. 82). However, any candidate for the flood must agree with the date and historical context described in Genesis. It cannot have happened in America, for instance. The Mesopotamian plain in the third millennium BC is thereby favored by most scholars because this is the place where the biblical patriarchs lived.

Numerous excavations have been made there, not primarily to find the flood but to gain insight into the Sumerian civilization. In 1929/8, when Sir Leonard Woolley found evidence of an ancient culture in Ur below a thick layer of clay, he thought to have found the flood supposed to having drowned an area of 400 miles long and 100 miles wide in the north-west of the Persian Gulf, which seemed to be confirmed by an excavation in Nineveh. But they were dated to about 3800 BC. Other excavations at Ur, Kish, Shuruppak, Uruk and Lagash also unearthed clay layers dated to about 2900 BC, but clear proof that they originated from the same flood is lacking. Furthermore, they were not important enough to displace, let alone decimate, the population (Fischer 2008 pp. 94-97; Keller 2015 pp. 22-30).

Fischer (2008 pp. 97-100) nevertheless thinks that the biblical flood occurred in this area and at this date. He attributes the disagreement of the dates – 2500 BC against 2900 BC – to some incorrect numbers in the Masoretic text, favoring those in the Septuagint, by which he arrives at 2978 BC. However, as mentioned in the previous section, the Masoretic numbers are the correct ones for reasons that will become evident in chapter 3.3. On the other hand, he rightly mentions (pp. 75-80) the meteorological and flat conditions of Mesopotamia, which make this plane of the Euphrates and Tigris prone to inundations. He reports that thirty major floods were recorded in and around Baghdad from 762-1906 AD. So it comes as no surprise that also during the third millennium BC there were deluges of similar or even greater scale and that Sumerian myths are referring to them.

Fischer indeed thinks that Utnapishtim, a Sumerian hero, could have been the historical Noah. As he points out (pp. 85-92, 105-117, 127-152), there are a lot of parallels between the Genesis flood account including Noah and the Sumerian tells. The Gilgamesh epic in particular mentions, for example, gods displeased with humanity, a man and his family being warned of an impending flood. To escape it, they built a boat and loaded it with animals. At the retreating of the flood, they came to rest on a hilly region, and so on.

But he rightly observes (p. 92) that contrarily to what most scholars conclude (e.g. Zeilinger 1986 p. 106; Van Schaik & Michel 2016 p. 82), this is no proof that the biblical flood story is a kind of plagiarism of Sumerian myths, which distorted and transcended the original events. He argues that Moses, the likely author of Genesis, may have had access to the royal libraries of Egypt or benefited from an oral tradition going down his ancestral lineage. If Genesis 1-11 is a revealed text like Revelation, this is even not necessary, though. So it is also possible that the author of the Gilgamesh epic was inspired by early Semitic writings or oral traditions or real events (Price 1997 pp. 64-71).

Given that the Masoretic numbers are correct, is it then possible to stretch the dates of the Exodus and/or the Temple of Solomon back in time to reconcile them with a flood at 2900 BC? This cannot be answered in this book. But what can be said is that the 2500 BC flood is only a slim part of the whole equation. As we are going to see, the genealogies hint to other dates and thereby to other floods, each of which contributes some detail to the overall picture. This is why the 2500 BC flood does not need to be global and having exterminated all of humanity. These details will be realized by the end-time flood of fire (sec. 3.1.1) and thereby does not have to be provided by the preceding floods as well. So just because the 2500 BC flood is apparently restricted to a small area does not invalidate it. It may even have been a very small flood affecting only one city like Kish, where indeed an inundation appears to have happened between 2400 and 2600 BC (Van Schaik & Michel 2016 p. 82; Dickin 2018).

3.1.5 Early Flood Scenarios

The long lifespans of the patriarchs almost reaching 1000 years as listed in Genesis 5 and 11 challenge all what is known from paleoanthropology, while they also reveal interesting mathematical relations, which is why it is legitimate to wonder whether they are constructed rather than natural numbers (Cassuto 1961 pp. 259-262; Holzer 1964 pp. 201-204). Others believe that they have been corrupted in the course of their textual tradition (Scharbert 1983 p. 76; Zeilinger 1986 p. 107; Etz 1993). Young-earth creationists take them literally, of course, but also some old-earth creationists (Ross 2001b pp. 117-125).

No doubt that the ages are indeed way too high, such that, here again, we can safely consider them as an open invitation to dig deeper. Waltke (2001 pp. 111-112) argues that they should be taken both as historical and symbolic, which goes in the right direction. Green (1890) was convinced that these genealogies are incomplete, that is, not all names were listed. When comparing the genealogies with others, for instance in the Gospels, there are indeed gaps in the listings (Allis 1943 p. 262; Ramm 1964 p. 220; Bonnette 2014 pp. 182-184). However, it is not correct to conclude from this that the genealogies offer no base to calculate the date of the flood, the birth of Adam, and so on. On the contrary: these gaps suggest that the explicitly named patriarchs can also be regarded as the firsts of a group, tribe, dynasty or whatever. This does not stand in contradiction with a literal reading, which depicts them as extremely high-aged patriarchs. Here again, we need not choose either one or the other possibility. Both a literal and a more subtle take are valid solutions. The literal view yields the above valid dates for Adam’s birth and Noah’s flood. The other solution yields other valid dates.

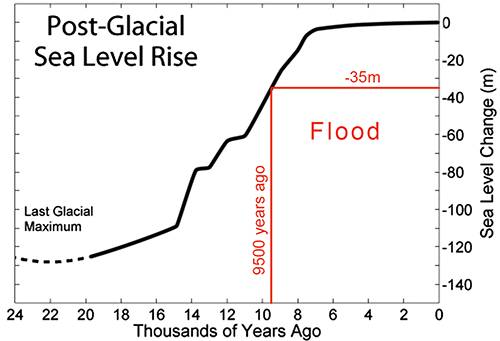

Assuming that the patriarchs are tribes or dynasties, then Adam is not the direct father of Seth but an ancestor. Idem for Seth and Enosh, and so on. The Hebrew ab can indeed mean both father and ancestor. In such a scenario, we have to assume that the dynasties succeeded one after another. In order to determine the time when the patriarchs were born, we thereby have to sum the ages from Adam to Terah, the father of Abraham, because Adam can be considered a prefigurative Abraham, with whom a new cycle begins after Terah (fig. 12). Thus we get 11’571 years (tab. 5), which – in order to obtain a date in BC – have to be added to the birth date of the literal (or late) Adam in 4188 BC. This way we obtain the birth date of an early Adam, which was in 4188BC + 11’571 = 15’759BC or roughly 18 ka. According to the same calculation, the corresponding early Noah was born 7625 years after the early Adam (tab. 5), that is, in 15’759 BC – 7625 = 8134BC. His flood took place 600 years later (Gen 7:6) in 7534 BC, say about 9500 ya.

Figure13: the flat bathymetry of the Persian Gulf suggesting major flood events some thousand years ago. The white area was flooded about 14’000 years ago and is at 80 meters below the actual sea level. The other levels indicate 60, 40 and 20 meters below actual sea level (Lambeck 1996).

As reported by archaeologist Jeffrey Rose (2010), there is evidence that the Persian Gulf was dry around 18 ka because of the last glacial maximum occurring largely around 22 ka when an important part of Earth’s water reserves were not stocked in the oceans but in enormous continental ice shields in the colder regions of the north and south. As a result, the sea level was about 120 meters lower compared to the present level (fig. 14), exposing large portions of the continental shelfs around the Earth. At the same time, climate was very dry on the Arabian Peninsula such that populations sought refuge in wet zones during MIS 2 (24’000 - 12’000 BC). One of these was the present-day seafloor of the Persian Gulf at the confluence of the Tigris, Euphrates, Karun and Wadi Batin, which alimented a freshwater lake. Furthermore, there have been numerous upwelling springs in this region (Gen 2:6), allowing the irrigation of possibly the first agricultural fields (Gen 3:17-19). Rose further mentions that numerous archaeological sites document the sudden appearance of settlements along Middle Holocene (~8000 BC) shorelines, suggesting that populations were displaced by the sea-level rise after the last glacial maximum.

Figure14: This diagram of the mean sea-level rise since the last glaciation reveals that a part in the Persian Gulf, lying about 35 meters under the actual sea level, was flooded about 9500 years ago (adapted from Fleming et al. 1998 p. 339).

So if this was the early flood linked to the early Noah, the date and place correspond rather well. However, it may not have been a catastrophic event that came by surprise drowning many people, as the sea level rose very slowly and the waters did not retire (Gen 8:1-14). But it is possible that another natural disaster such as a tsunami, storm or river flood may suddenly have broken in, which would have had a devastating effect because this is one of the world’s flattest regions.

Pearce (1987 pp. 15, 80) believes that the flood happened in the Armenian highland, which is a possible candidate for Eden (sec. 2.1.3) and where also the ark came to rest near the mount Ararat (Gen 8:4). There is indeed geological evidence from sediments of Lake Van that there were abundant precipitations largely around 8500 BC possibly already beginning 1000 years earlier (Dickin 2018), which may have affected this region even more than the Mesopotamian plain. Pearce further argues (pp. 47-63) that Adam’s tilling in the garden of Eden (Gen 2:15) refers to man’s first horticulture and farming activities, which did not begin in the Mesopotamian plain but in the Fertile Crescent, more precisely, in the catchment area of the Euphrates and Tigris, in other words, in the northern Levant or Armenian highland. However, he dates this beginning to 12 ka, which is not a date that can be extracted from Genesis.

The date of the first agricultural practices is controversial from an archaeological point of view. For a long time, the credo was that the domestication of plants and animals started some 10 ka in the Fertile Crescent, where the wild ancestors of most of the Neolithic crops grew and the first settlements together with domesticated plants were found (Nesbitt 2002). The difference between wild and domesticated grains was based on morphology. Subsequently, the oldest rye grains have been dated to about 12.5 ka based on this criterion. However, increasing evidence emerged that humans were already tilling the ground perhaps 4000 years or more before the manifestation of morphological indicators of plant domestication (Zeder 2011), thus coming much closer to 18 ka. There is also a time lag of several thousand years between sedentism and these manifestations, suggesting that sedentary foraging is a necessary first step for initial attempts at horticulture. The best evidence for early sedentism comes from temperate zones like the northern Levant, while in tropical rainforests and the Arctic mobility has persisted longer (Dow & Reed 2015).

The Black Sea deluge is another flood scenario proposed by Ryan et al. (1997). They argued that a sudden inflow of the Mediterranean waters into the Black Sea through the Bosporus occurred about 7600 ya, again due to the sea-level rise after the last glaciation. Later, they revised this date to 8800 ya (Ryan et al. 2003), which comes close to 9500 ya but not close enough. Also the place of the flood, the coast of the Black Sea, does not really fit the biblical description. Furthermore, subsequent studies argue that this flood was not catastrophic but extended over several decades (Yanko-Hombach et al. 2011; Yanchilina et al. 2017) and it did not retire again (Gen 8:1-14).

References

- Allis, O. T. (1943). The Five Books of Moses. Philadelphia: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company.

- Armbruster, J.-B., Bavaud, G., Chavannes, H., de Fiores, S., Jobert, P., & Koehler, T. (1986). Marie et la fin des temps: approche historico-théologique (Vol. 3). Paris: O.E.I.L.

- Bauckham, R. (1993). The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Cambridge University Press.

- Blocher, H. (1984). In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis. (D. G. Preston, Trans.) Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press.

- Bonnette, D. (2014). Origin of the Human Species (3rd ed.). Ave Maria: Sapientia Press.

- Cassuto, U. (1961). A Commentary on the Book of Genesis: From Adam to Noah (Vol. 1). (I. Abrahams, Trans.) Jerusalem: The Magness Press.

- Cassuto, U. (1964). A Commentary on the Book of Genesis: From Noah to Abraham (Vol. 2). (I. Abrahams, Trans.) Jerusalem: The Magness Press.

- Clines, D. J. (1972). Noah’s Flood: The Theology of the Flood Narrative. Faith and Thought, 100(2), 128-142.

- Dembski, W. (2009). The End of Christianity: Finding a Good God in a Evil World. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group.

- Denzinger, H. (1955). The Sources of Catholic Dogma (13th ed.). (R. J. Deferrari, Trans.) Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications.

- Dickin, A. (2018). New Historical and Geological Constraints on the Date of Noah's Flood. Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 70(3), 176-177.

- Dow, G. K., & Reed, C. G. (2015). The origins of sedentism: Climate, population, and technology. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 119, 56-71.

- Etz, D. V. (1993). The numbers of Genesis V 3-31: a suggested conversion and its implications. Vetus Testamentum, 43(2), 171-187.

- Finegan, J. (1998). Handbook of Biblical Chronology: Principles of Time Reckoning in the Ancient World and Problems of Chronology in the Bible (2nd ed.). Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc.

- Finkelstein, I., & Silberman, N. (2001). The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Text. New York: The Free Press.

- Fischer, R. J. (2008). Historical Genesis: From Adam to Abraham. University Press of America.

- Fleming, K., Johnston, P., Zwartz, D., Yokoyama, Y., Lambeck, K., & Chappell, J. (1998). Refining the eustatic sea-level curve since the Last Glacial Maximum using far-and intermediate-field sites. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 163(1-4), 327-342.

- Free, J., & Vos, H. (1992). Archaeology and Bible History (Revised ed.). Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Green, W. H. (1890). Primeval chronology. Bibliotheca sacra, 47, 285-303.

- Hill, C. A. (2002). The Noachian Flood: Universal or Local? Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 54(3), 170-183.

- Hoffmeier, J. K. (1997). lsrael in Egypt : The Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus Tradition. Oxford University Press.

- Holzer, J. (1964). Und Gott sprach: Biblischer Schöpfungsbericht und modernes Wissen. Bonn: Verlag des Borromäusvereins.

- Hughes, J. (1990). Secrets of the Times: Myth and History in Biblical Chronology. Sheffield: JSOT Press.

- Keller, W. (2015). The Bible as History (2nd Revised ed.). (W. Neil, Trans.) New York: William Morrow.

- Lambeck, K. (1996). Shoreline reconstructions for the Persian Gulf since the last glacial maximum. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 142(1-2), 43-57.

- Laurentin, R. (1982). Les Évangiles de l'Enfance du Christ: Vérité de Noël au-delà des mythes. Paris: Desclée.

- Martelet, B. (1976). Marie de Nazareth: Celle qui a cru. Paris: Éditions Saint-Paul.

- Morris, H. M. (Ed.). (1974). Scientific Creationism. San Diego: Creation-Life Publishers.

- Nesbitt, M. (2002). When and where did domesticated cereals first occur in southwest Asia? In R. Cappers, & S. Bottema (Eds.), The Dawn of Farming in the Near East: Studies in early Near Eastern production, subsistence, and environment (2nd ed., pp. 113-132). Berlin: Ex Oriente.

- Pearce, V. (1987). Who Was Adam? (2nd ed.). Attic Press.

- Price, R. (1997). The Stones Cry Out. Eugene: Harvest House Publishers.

- Ramm, B. (1964). The Christian View of Science and Scripture. The Paternoster Press.

- Rose, J. I. (2010). New light on human prehistory in the Arabo-Persian Gulf Oasis. Current Anthropology, 51(6), 849-883.

- Ross, H. (2001b). The Genesis Question: Scientific Advances and the Accuracy of Genesis (2nd ed.). Colorado Springs: NavPress.

- Ryan, W. B., Major, C. O., Lericolais, G., & Goldstein, S. L. (2003). Catastrophic flooding of the Black Sea. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 31(1), 525−554.

- Ryan, W. B., Pitman, W. C., Major, C. O., Shimkus, K., Moskalenko, V., Jones, G. A., . . . Sakinç, M. (1997). An abrupt drowning of the Black Sea shelf. Marine Geology, 138(1-2), 119–126.

- Ryan, W., & Pitman, W. (1998). Noah's Flood: The New Scientific Discoveries About the Event That Changed History. Simon & Schuster.

- Scharbert, J. (1983). Genesis 1-11. Würzburg: Echter Verlag.

- Scheeben, M. J. (1946). Mariology (Vol. 1). (T. Geukers, Trans.) B. Herder Book Co.

- Van Schaik, C., & Michel, K. (2016). The Good Book of Human Nature : An Evolutionary Reading of the Bible. New York: Basic Books.

- Waltke, B. K. (2001). Genesis: A Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Whitcomb, J., & Morris, H. (1961). The Genesis Flood: The Biblical Record and its Scientific Implications. Presbyterian & Reformed Publishing.

- Whorton, M., & Roberts, H. (2008). Holman QuickSource Guide to Understanding Creation. Nashville: B&H Publishing Group.

- Yanchilina, A. G., Ryan, W. B., McManus, J. F., Dimitrov, P., Dimitrov, D., Slavova, K., & Filipova-Marinova, M. (2017). Compilation of geophysical, geochronological, and geochemical evidence indicates a rapid Mediterranean-derived submergence of the Black Sea's shelf and subsequent substantial salinification in the early Holocene. Marine Geology, 383, 14-34.

- Yanko-Hombach, V., Mudie, P., & Gilbert, A. S. (2011). Was the Black Sea Catastrophically Flooded during the Holocene? - geological evidence and archaeological impacts. In J. Benjamin, C. Bonsall, C. Pickard, & A. Fischer (Eds.), Submerged Prehistory (pp. 245–262). Oxford Books.

- Zeder, M. A. (2011). The Origins of Agriculture in the Near East. Current anthropology, 52(S4), S221-S235.

- Zeilinger, A. (1986). Das Alte Testament verstehen I: Die fünf Bücher Mose oder der Pentateuch. Konstanz: Christliche Verlagsanstalt.

This site is hosted by Byethost

Copyright © Vierge Press

| < | > |