2.1 Adam and Eve

Abstract

It is shown that the significance of Adam and Eve is multilayered. So their creation and their sojourn in the garden of Eden is not a simple and exclusive story of our first parents. It is indeed easy to show that chapters two and three of Genesis are referring to multiple events and times in history, including all human ancestors, Christ and even the angels.

Contents

The Parallel Adam/Christ

A Celestial and Terrestrial Adam

Several Paradises

Anachronism

References

Site Navigation

2.1.1 The Parallel Adam/Christ

St. Paul states that Christ has come into this world in order to repair the fault of Adam (Rom 5:12-19; 1 Co 15:22). So one should expect that the Eden account foreshadows Christ through the life of Adam. There are indeed several elements that are traditionally considered to refer to Jesus and his mother Mary, which I will resume here shortly and non-exhaustively. This begins right from the start, the creation of Adam out of dust:

And the Lord God formed the man from the dust of the ground and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the man became a living being (Gen 2:7).

This dust must not be taken literally, as shown by Scheeben (1948 p. 66), who states that “from time immemorial, Mary’s spotlessness has had as its figure and symbol the immaculate earth from which Adam was formed” in order to show that Jesus’s mother was exempt of original sin. He also cites a text from the Council of Frankfurt held in 794: “Christ is born of the Virgin, indeed of a better earth which is animated as well as immaculate”. An even older testimony of this thought is given by St. Andrew:

The Redeemer of the human race - as I said - willed to arrange a new birth and re-creation of mankind: like as under the first creation, taking dust from the virginal and pure earth, wherein He formed the first Adam, so also now, having arranged His Incarnation upon the earth, – and so to speak, in place of dust – He chooses from out of all the creation this Pure and Immaculate Virgin and, having re-created mankind within His Chosen-One from amidst mankind, the Creator of Adam is made the New Adam, in order to save the old.

Further on, Scheeben (p. 79) also cites St. John Damascene:

Today Eden received the rational paradise of the new Adam in which the condemnation was lifted, and in which the tree of life was planted. No access to this paradise was open to the serpent. For the only begotten Son of God formed Himself into a man from this virgin and this pure earth.

So the breath of life that God blew into Adam’s nostrils prefigures the Holy Spirit, by which Jesus was miraculously conceived without a biological father (Lk 1:34-35). And the garden of Eden, whose pure, still not cursed earth (Gen 3:18) is taken to form Adam, is an image of Mary, the Mother of Jesus. The meaning of the earth thus clarified, one has to conclude that the real sense of Genesis 2:7 is that, by analogy, the first Adam was also formed inside the womb of a mother rather than directly by dust. According to paleontology, Homo sapiens is indeed a descendant from Homo erectus or neanderthalensis, as will be discussed in chapter 3.2. According to Bonnette (2014 pp. 174-175), Adam and Eve could be twins. If true, they would have risen by their mother, which is possible because of the relatively slim differences from one species to the next. In fact, DNA varies very little from one species to the next, which also shows strong evidence for common descent. In any case, Mary is prefigured by the prehuman mother who gave birth to Adam.

Then, God planted a garden in Eden and created all animals out of dust like Adam (Gen 2:8-20). This implies the same as for Adam: all species had close ancestors of previous species, confirming Darwin’s theory of descent. However, as will be discussed in chapter 2.5, this does not mean that the emergence of all species can be explained naturally by selection because they prefigure the ultimate goal of the physical world: the incarnation, which is undeniably a miracle and the key event of the entire evolution foreshadowed by many sub-events (fig. 9).

Next, Adam is with the animals and gives them names (Gen 2:20). This also has a parallel with Jesus, who was in the desert surrounded by animals during forty days after his baptism (Mk 1:13). He ate nothing during these days, at the end of which he became hungry and was tempted by the devil (Lk 4:1-13) just as Adam (Gen 3:1-6). But unlike Adam, Jesus resists Satan (Blocher 1997 pp. 46-47). In this context, some early fathers taught that the appearance of the angel Gabriel to Mary (Lk 1:26-38) – the Annunciation – is the reversal of the appearance of Satan, whereby the first Eve was tempted (Justin Martyr, Apologia, ch. 100; Irenaeus of Lyons, Against Heresies, Book 3, ch XXII, par. 4; Tertullian, On the Flesh of Christ 17:4; Augustine, Christian Combat 22:24).

Still before this temptation (Gen 3), God caused a deep sleep upon Adam, removed a rib from him and formed Eve out of it to become his wife (Gen 2:21-25). This refers to the dead of Jesus at the cross, beneath which stood Mary, whom Jesus did not call mother but woman (Jn 19:26), thus becoming the new Eve. The removing of the rib corresponds to the piercing of his side, from where water and blood flowed out (Jn 19:34), making Mary understand, still before all the apostles, the purpose of her Son’s death. Analogously, the awakening of Adam (Gen 2:23) corresponds to Jesus’s resurrection. It is likely that Mary was the only one who stood at Jesus’s side at this event because the apostles abandoned him (Mk 14:27). She thus became Jesus’s closest ally and helper (Gen 2:18).

Mary as the bride of God, or new Eve, can also simply be inferred from the fact that Jesus was conceived by the Holy Spirit (Lk 1:35), who is God:

O most sacred daughter of Joachim and Anna [Mary’s parents], who wast hidden from principalities and powers as well as from the fiery darts of the devil, who layest in the bridal bed of the Holy Ghost and wast kept without stain, in order to become the bride of God and God’s mother by nature (Scheeben 1948 p. 79 citing St. John of Damascene).

So via the Holy Trinity, Mary the new Eve is not only the Mother but also the Bride of the new Adam, Jesus, through his divine nature (Scheeben 1946 p. 162; Scheeben 1948 pp. 62-70). Mary thus became the Mother, similar to God the Father, of all humans born in the faith in Jesus, who is the First-born of this new generation (Lk 2:7; Col 1:15; Rev 1:5), the eldest of a multitude of brothers (Rom 8:29) born and adopted by the Holy Spirit (Gal 4:4-7), the new Adam exempt from all sin (Rom 5:12-19). Finally, Mary is also a child of this big family because she has herself faith in her son. In this spiritual sense, Jesus and Mary are also brother and sister, like Adam and Eve are possibly biological siblings. On the other hand, various passages compare Christ to the Spouse and the people of God to his bride (Mk 2:19; Jn:29; Eph 5:22-33; 2 Cor 1:2, etc.). It seems that this way the word of Jesus “Whoever does the will of God, that person is my brother, and my sister, and my mother” (Mk 3:35) is perfectly realized.

| Father | Mother | Child(ren) | |

| Birth of Adam | God the Creator | prehuman mother | Adam |

| Birth of humanity | Adam | Eve | humanity |

| Birth of Christ | Holy Spirit | Mary Mother of God | Christ-man |

| Birth of Christians | Christ-God | Mary the new Eve | Christians |

Table 4: The analogies between Adam/Eve and Christ/Mary

Another important parallel is the so-called protevangelium. After having seduced Adam and Eve, the serpent is sentenced to creep on its belly (Gen 3:1-14). Furthermore, still addressing himself to the serpent, God prophesizes:

I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and her offspring. He shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel (Gen 3:15).

“He” in the Hebrew text is masculine as well as “his” (contrarily to the Vulgate), thus not referring to the woman but to her offspring (or seed), which is only represented by one son instead of several sons of the woman as in Galatians 3:16. Since offspring naturally proceeds from a man, this offspring of the woman proceeds in a supernatural way, that is, from the virgin Mary without a man. The deadly crushing of the serpent’s head as opposed to its bite into the heel expresses the inequality of power between the woman’s offspring and the serpent. In fact, the serpent was only able to wound our Savior through his bodily death at the cross while the serpent has been eternally cast into hell by this sacrifice (Scheeben 1946 pp. 241-244; Martelet 1976 p. 22; Blocher 1984 p. 194).

A lot of other details could be mentioned regarding the parallel between Adam and Christ. The main purpose here is to show that the Eden account is not one-dimensional, that is, referring exclusively to the first humans. It’s a multilayered account referring to several events at different times. In particular, it also echoes a very distant past, those of the angels, which will be discussed in the next section.

2.1.2 A Celestial and Terrestrial Adam

At first sight, the Eden account looks like a fairy tale written for children. All animals are eating herbs (Gen 1:30), so even predators like lions and wolves. There is a tree of life as well as a tree of the knowledge of good and evil in the middle of the garden (Gen 2:9). A speaking snake is telling lies to Eve (Gen 3:1-5), which involves a flagrant contradiction: since the snake is able to speak, it is traditionally taken as a fallen angel. However, this involves that it is not an animal. On the other hand, it is unambiguously presented as an animal and thereby should not be able to speak a human language. Assuming that the text accurately relates historical facts, this paradox can only be reasonably resolved if we accept that the serpent refers to both the devil and the animal.

If the serpent has such a twofold meaning, then also all other animals and in particular Adam. In other words, Adam represents both the angels and humans. In the first place, the environment in which Adam lived – the garden of Eden or paradise – is indeed a place in the heavenly realm, which is just echoed by some terrestrial paradises. This is also alluded to by St. Augustine:

On this subject [paradise] there are three main views. According to the first, some wish to understand paradise only in a material way. According to the second, others wish to take it only in a spiritual way. According to the third, others understand it both ways, taking some things materially and others spiritually. If l may briefly mention my own opinion, I prefer the third (De Genesi Ad Litteram, VIII, 1).

The term paradise is a loan word from Persian meaning verdant garden used in the Septuagint to translate the Hebrew term for the garden of Eden in the first chapters of Genesis and other passages in the Bible. Over the course of the Second Temple Period, paradise was no longer simply the place where Adam and Eve lived but extended to the place where the souls of the deceased righteous will reside eternally (Wright 2000 p. 188). This is confirmed by Jesus’s inviting of the penitent thief into paradise shortly before his dead on the cross (Lk 23:43).

An indirect hint to the heavenly realm of Eden is given in Ezekiel 28:12-19. Traditionally, this story of the king of Tyre is seen as referring to Satan, who turned away from God by pride, which caused his banning from the mountain of God (Parente 1994 pp. 57-58), even though Blocher (1997 p. 44) claims that most modern commentators do not support this view. However, the king is indeed compared to a splendid and blameless cherub (angel) who originally lived in the garden of Eden and was covered with “every precious stone” (Ez 28:13), from where a connection is made to the new Jerusalem (Rev 21:19-20). This city is clearly spiritual as it comes down from heaven, the river of the water of life flows in it and in its middle is the tree of life. As discussed in section 2.1.1, this is Eden restored, from where Adam was chased but whose fault Christ has undone (Bauckham 1993 pp. 133-135; Morris 1994 p. 128; Waltke 2001 pp. 103-104; Kahn 2007 p. 1). So by extension back into the past, the initial Eden was spiritual as well. Furthermore, Jesus clearly states that his kingdom is not of this world (Jn 18:36).

Does this mean that Adam and Eve were hurled down on earth from heaven because of their sin and that their souls have been cast into human bodies created by the devil, the master of darkness not created by God but being his adversary since eternity? This world view is called Priscillianism and is an attempt to explain evil, the existence of the material world and living beings with physical bodies. However, this view stands in direct contradiction with the claim that all things and beings, demons included, not only have been created in the beginning of time but also in a state of complete integrity (Gen 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25, 31; CCC 391), which is why it was condemned by the Church at the Council of Braga II in 561 (Denzinger 1955 nos. 235-238, 241-243, 428).

The Eden account mentions animals in the garden (Gen 2:19-20). Does a spiritual garden imply that there are animals in heaven? I guess many pet owners hope and believe that there is a place in heaven for their loved companions after their death (Lk 12:6). But the question here is whether there were also animals in paradise from the start. As discussed in section 1.4.3, there are celestial plants in paradise, so there may indeed be also celestial animals. If true, however, they certainly don’t look like terrestrial animals. A hint to this is the snake that lost its paws after the fall (Gen 3:14).

In evolutionary terms, snakes indeed lost their paws, being descendants of four-legged lizards (Klotz 1972 pp. 446-447), contrarily to what Blocher (1984 p. 179) believes. So one may argue that before the fall not only snakes but all animals looked different and that suddenly lions, wolves and other predators got canines and claws after the fall. Thomas of Aquinas (Summa theologica, part 1, question 96, article 1) thinks that “The nature of animals was not changed by man’s sin”, which is obvious and thereby seems to be a widespread view (Holzer 1964 p. 89). But then one has to ask oneself what does it mean that all land animals did eat herbs before the fall (Gen 1:30), which will be discussed in chapter 2.4.

While celestial animals have definitely not the same form as their counterparts on earth, it is not quite adequate to call them animals. Since they are spiritual beings, they are indeed angels. But among the angels there is a similar hierarchy than in the animal kingdom. They have been created with different tasks and varying responsibilities, which implies that there is a large hierarchy among angels, as suggested by Colossians 1:16. In fact, there is a large consensus that angels are subdivided into different categories in a similar way than animals, even though there is divergence of opinion on the exact hierarchical structure (Parente 2006 pp. 48-56). St. Thomas and others even think that every individual angel is specifically distinct from each other, that is, similar to the difference of each animal species to each other (Parente 1994 p. 23; Aquilina 2006 p. 9).

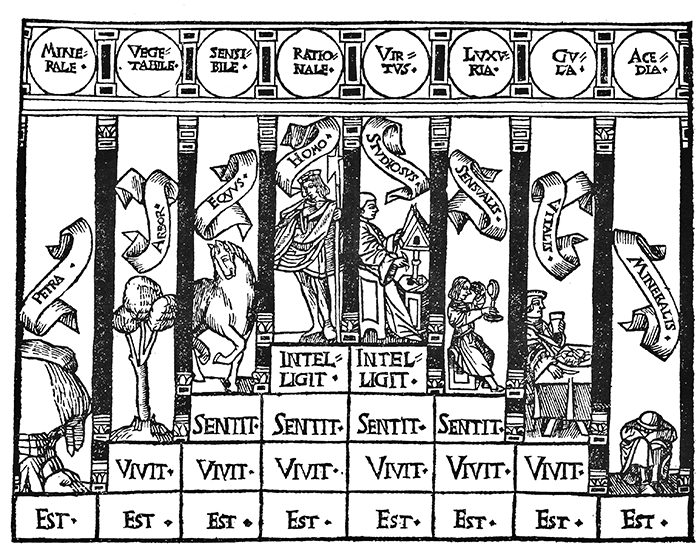

St. Gregory thinks that just as humans are over the beasts, the angels are over man and the archangels over the angels and so on. St. Thomas makes a similar comparison reaching out even to plants (Parente 1994 pp. 48-56; Aquilina 2006 pp. 36-38). On the other hand, man was created in the image of God (Gen 1:26), just as certainly also the angels. So humans belong to both orders as they are composed of both spirit and body (Bonnette 2014 p. 146). This is sustained by the validity of the Eden account for both angels and humans, which rather suggests that the difference between angels and humans is not so abysmal. Maybe the difference is more like something analogous to the relation suggested by figure 10.

Figure10: Comparison between the natural and human hierarchy proposed by an unknown medieval artist.

Kreeft (1995 p. 120) thinks that, within the angelic order, Satan was the most powerful among all angels and rebelled against God out of pride because he resented being number two after God. The serpent is indeed craftier than any other beast (Gen 3:1). However, it is presented as an animal, not as a human. Extrapolating this to the spiritual world rather suggests that the angel represented by Adam was number two after God, and Satan number three or a lower being. But he was certainly a high-ranked angel otherwise he would not have been followed by his demons.

2.1.3 Several Paradises

The term Adam, simply meaning a male or the human race in Hebrew, is also referring to different persons and entities in the past limited to human history in the contexts of both the expulsion from paradise and the flood. So just as we have several Adams, there are also several paradises and floods, of which we have to determine the location and historical context.

There have been numerous attempts to locate Eden based on its description in Genesis 2:10-14, which mentions four rivers. Two of them, the Euphrates and Tigris (Hiddekel in Hebrew) are well known from Iraq. However, they flow together, whereas Genesis 2:10 is the most often rendered as: “A river flows out of Eden to water the garden, and from there it divides and becomes four branches.” Let’s take a closer look at the verb yasa, which is the most often translated as go out. This is not always the case yet. In Genesis 8:7 the raven sent out from the ark went to and fro until it found dry ground. Here, yasa is used for both went to and went fro. So Genesis 2:10 may also be rendered as: “A river flows into Eden to water the garden...”. In order to make sense to the rest of the sentence, one has to look upstream the present-day Shatt Al-Arab, which divides into the Euphrates and Tigris near the city of Al-Qurnah above the former Eden. The noun ros translated as branches indeed means head or beginning and thereby can also be translated as sources. In this case, Eden was located somewhere above the delta of the Shatt Al-Arab.

This does not mean that yasa translated as went out is false. This possibility just points to another valid solution that takes into account that a river can be divided downstream. This can happen naturally in a delta when the river empties in the sea, which contributes to the view that Eden was located above the delta of the Shatt Al-Arab. But another solution is possible also: canals constructed to irrigate agricultural fields, as still is the case in present-day Iraq (Blocher 1984 p. 118; Claeys 1987 pp. 271-272; Fischer 2008 p. 12), which further supports Eden’s location in Mesopotamia. The noun ros (head) in this context then has to be understood as the mouth of the river, towards which it is heading, as one could say in English.

If nahar (river) in Genesis 2:10 is taken as a groundwater flow like in Job 28:11, Eden can even be located in the Armenian highlands where the Euphrates and Tigris have their catchment area and sources. This is reminiscent of Genesis 2:6, which mentions water emerging out of Eden’s ground like a spring, and various depictions of restored Eden, from which a stream of water flows out (Ps 46:4; Ez 47:1-12; Jl 3:18; Zec 14:8; Rev 22:1-2). Noah’s Ark came to rest near the mount Ararat in the Armenian highlands, where humanity started a new beginning after the failed one of Adam. It is indeed thought that this region has been inhabited by the first settlers and agriculturalists in the Neolithic (Blocher 1984 pp. 118-119). So this place also contributes to the image of Eden restored (Cassuto 1961 pp. 114-115).

But where are the other two rivers, the Gihon and the Pishon (Gen 2:11-13)? This is the subject of much speculation, as they have been associated with almost all known rivers on Earth (Albright 1922). Archaeologist Juris Zarins claims to have discovered Pishon on satellite images as a dried out fossil river once flowing from the south-western part of Mesopotamia into the Shatt Al-Arab and known to Saudis and Kuwaitis as the Wadi Kimah and Wadi Batin. He thinks that this region was once rich in bdellium and gold, thus corresponding to Havilah (Gen 2:11-12). On the other hand, he identifies the Gihon as the Karun still flowing from Iran into the Shatt Al-Arab. He thus declines the traditional view that the land of Cush, around which it flows (Gen 2:13), is Ethiopia (Hamblin 1987). This interpretation is certainly also a valid solution, but it’s not the primary one.

For numerous plausible reasons, which cannot be discussed here, archaeologist William F. Albright (1922) suggested that Cush and Havilah are indeed locations in eastern Africa. If true, the corresponding rivers have to be identified with the White and Blue Nile, which have their sources in this region. However, these rivers do not encompass any area in eastern Africa, as the verb sabab is often rendered. It can also just mean to turn in the sense of changing the direction. So “meanders the whole land...” like a river does – especially in a plain – would be a more adequate translation. In fact, there are some flagrant similarities between these two rivers and those of Mesopotamia. After rising in the mountains, they unite in a vast plain as one river, which empties into the sea before forming a vast delta that was and still is intensively exploited agriculturally. These plains and deltas have been the scenes of the first civilizations: the Egyptians and Babylonians (Cassuto 1961 pp. 116-119).

2.1.4 Anachronism

An important issue in the Eden narrative is the apparent anachronistic order of the whole evolution resumed in the beginning of chapter 2: the creation of matter is mentioned first (Gen 2:4-6) followed by the creation of man (Gen 2:7) before the plants (Gen 2:8-9) and the animals (Gen 2:18-20). Therefore, the creation of Adam seems to be mentioned prematurely. One can attribute this to the ignorance of the author. However, the correct chronological order – matter, coevolution of plants and animals, man – is already given in the creation account. So it is unlikely that this anachronism is an error of the author, unless one argues that the Eden account has been written by a different author. It would then be just a second creation account based on different pagan sources, as advocated by many scholars (Allis 1943 pp. 21-123; Scharbert 1983 pp. 5-13; Zeilinger 1986 pp. 23-25). I will not embark here on this so-called documentary hypothesis or on more recent developments in this direction.

Other authors do not assume that Genesis is mythology but nevertheless propose otherwise untenable solutions. Commentator Coffman, for instance, argues that all plants were only created as seeds on the third day. So when Adam was created, the seeds were already in the soil but had not grown yet because there was still no moisture (Gen 2:5). However, this explanation only works if literal 24-hour creation days are assumed, which is not at all the case. Other commentators (Barnes; Keil & Delitzsch) claim that they did not grow at every place on Earth but only locally in the garden of Eden, spreading thereafter over the whole planet. Still others (Kruger 1997) think that the plants of the garden of Eden were special field plants destined to agriculture and thereby were not created on the third day but only after Adam in order to allow him to grow and use them as food.

There is certainly some truth in this last interpretation if the garden of Eden is restricted to Mesopotamia, the plain of the Tigris and Euphrates, where the first civilizations appeared. In fact, the people who settled there irrigated the surrounding desert with the water of these rivers to cultivate bred field plants in the Neolithic. This was the first time that humanity practiced breeding of plants and animals (Zeder 2011). So in a sense they did not exist before humans. Thus, the plain was transformed into a little paradise for the humans at this time, as discussed in the previous section. But Adam is also referring to the very first humans and even to its ancestors, who lived millions of years ago and did not practice breeding of plants.

As for the animals, another frequently proposed solution is to use the pluperfect tense for the Hebrew verb yatsar (to form) in Genesis 2:19. The text would then just refer to the animals that already had been formed (Coffman; Pulpit; Ross 2001b pp. 73-74). According to Claude Mariottini, Professor of Old Testament, some Bible translations (ESV, GWN, NIV) indeed render the text in this manner. However, there seems to be no consensus among scholars regarding the Hebrew grammar of this verb, even though the big majority uses the imperfect tense formed (ASV, HCSB, JPS, KJV, NAB, NAS, NJB, NET, LB, RSV, TNK).

In any case, when the whole context is taken into account, one must conclude that the intention of the author clearly was to say that the animals were created after Adam because God did not want him to be alone and afterwards decided to give him a help, that is, the animals and later the woman (Gen 2:18-23). So if at first he was alone, no animals were around at this stage, neither within his immediate vicinity nor elsewhere, which hints to an obvious paradox and thereby at the same time invites us to dig deeper in order to solve it.

The principle is the same as for the other apparent anachronisms we encountered so far. The first anachronism appears in the context of Genesis 1:1, mentioning earth created in the beginning. As summarized by rule number one (sec. 1.1.6), this is a vertical chronology, which steps over the horizontal chronology by referring to several earthlike objects including the planet Earth created much later relative to the beginning. But the main object is the whole physical world, which has indeed been created in the beginning. So no anachronism is present. The next anachronism concern highly evolved plants, which is also making part of a vertical chronology including the very first monocellular organisms that can live without sunlight and even celestial plants (sec. 1.4.3). Then, the birds also seem to be mentioned prematurely. But they are again part of a vertical chronology including flying insects, fish and angels (sec. 1.5.2).

So it is obvious that Adam is also part of such a vertical chronology including the angels, Christ, a late and early Adam, the first human and its several ancestors, as will be discussed in part 3. The main “object” or better the main protagonist of this chronology is the angel who has been put above all others in the angelic order (sec. 1.1.2). He has been created after the creation of the spiritual world represented by the lifeless earth, for which again the Hebrew erets is used (Gen 2:4-7). Only thereafter the other angels represented by the animals were created (Gen 2:18-20).

When chapter 2 of Genesis is applied exclusively to the terrestrial order, then the first humans are not represented by Adam but by Eve, who was created after the Earth, plants and animals (Gen 2:21-25), so in the correct chronological order. In fact, it is Eve who is called “The mother of all living” (Gen 3:20). Nowhere in the Pentateuch Adam is called The father of all living, despite its preference for patriarchs. So this privilege is certainly not attributed to Eve just by coincidence. Furthermore, Adam as a masculine figure is more neuter with regard to gender. In fact, angels are genderless because, being immortal, they do not reproduce (Aquila 2006 p. 9), which is why they are never represented in the Bible by women.

As explained in the introduction, Genesis is a text that has merged together several levels. As a result, not every detail of the text needs to have a meaning for every level. So it is important to accurately assign the right details to the different levels. For instance, the creation of Eve is probably meaningless when applied to the spiritual world because they don’t reproduce. So there are no women among the angels. Also the names of the rivers and other details may not have any meaning for the spiritual world.

References

- Albright, W. F. (1922). The Location of the Garden of Eden. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, 39(1), 15-31.

- Allis, O. T. (1943). The Five Books of Moses. Philadelphia: The Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Company.

- Aquilina, M. (2006). Angels of God : the Bible, the Church, and the Heavenly Hosts. Cincinnati: Servant Books.

- Bauckham, R. (1993). The Theology of the Book of Revelation. Cambridge University Press.

- Blocher, H. (1984). In the Beginning: The Opening Chapters of Genesis. (D. G. Preston, Trans.) Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press.

- Blocher, H. (1997). Original Sin: Illuminating the Riddle. Leicester: Apollos.

- Bonnette, D. (2014). Origin of the Human Species (3rd ed.). Ave Maria: Sapientia Press.

- Cassuto, U. (1961). A Commentary on the Book of Genesis: From Adam to Noah (Vol. 1). (I. Abrahams, Trans.) Jerusalem: The Magness Press.

- Claeys, C. (1987). Die Bibel bestätigt das Weltbild der Wissenschaft. Stein am Rhein: Christiana-Verlag.

- Denzinger, H. (1955). The Sources of Catholic Dogma (13th ed.). (R. J. Deferrari, Trans.) Fitzwilliam: Loreto Publications.

- Fischer, R. J. (2008). Historical Genesis: From Adam to Abraham. University Press of America.

- Hamblin, D. J. (1987). Has the Garden of Eden been located at last? Smithsonian, 18(2), 127-135.

- Holzer, J. (1964). Und Gott sprach: Biblischer Schöpfungsbericht und modernes Wissen. Bonn: Verlag des Borromäusvereins.

- Kahn, P. W. (2007). Out of Eden: Adam and Eve and the Problem of Evil. Princeton University Press.

- Klotz, J. W. (1972). Genesis and Evolution (2nd ed.). Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House.

- Kreeft, P. J. (1995). Angels and Demons: What Do We Really Know about Them? San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- Kruger, M. J. (1997). An Understanding of Genesis 2:5. Creation Ex Nihilo Technical Journal, 11(1), 106-110.

- Martelet, B. (1976). Marie de Nazareth: Celle qui a cru. Paris: Éditions Saint-Paul.

- Morris, J. D. (1994). The Young Earth. Green Forest: Master Books.

- Parente, P. P. (1994). The Angels: In Catholic Teaching and Tradition. Charlotte: TAN Books.

- Ross, H. (2001b). The Genesis Question: Scientific Advances and the Accuracy of Genesis (2nd ed.). Colorado Springs: NavPress.

- Scharbert, J. (1983). Genesis 1-11. Würzburg: Echter Verlag.

- Scheeben, M. J. (1946). Mariology (Vol. 1). (T. Geukers, Trans.) B. Herder Book Co.

- Scheeben, M. J. (1948). Mariology (Vol. 2). (T. Geukers, Trans.) B. Herder Book Co.

- Waltke, B. K. (2001). Genesis: A Commentary. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Wright, J. E. (2000). The Early History of Heaven. Oxford University Press.

- Zeder, M. A. (2011). The Origins of Agriculture in the Near East. Current Anthropology, 52(4), 221-235.

- Zeilinger, A. (1986). Das Alte Testament verstehen I: Die fünf Bücher Mose oder der Pentateuch. Konstanz: Christliche Verlagsanstalt.

This site is hosted by Byethost

Copyright © Vierge Press

| < | > |